Four Horsemen of Cyber Reunite at the RSA ConferenceFour Horsemen of Cyber Reunite at the RSA Conference

Paul Nakasone. Timothy White. Stephen Davis. Jen Easterly. The quartet who drafted plans for US Cyber Command discussed their shared history in cyber defense.

SAN FRANCISCO -- RSA CONFERENCE -- Faced with the rising threat of cyberattack, it took a cadre of US military and intelligence agency officers to put together a cohesive cyber defense and operations plan under the Department of Defense. Drawn from multiple branches of American armed forces, the US Cyber Command formally got its start in May 2010.

On Wednesday, four key players in Cyber Command’s evolution came together at the RSA Conference in San Francisco.

Taking the stage were Retired Army General Paul Nakasone, former director of the National Security Agency (NSA), and a former commander of US Cyber Command; Retired Vice Admiral Timothy White, former commander, US 10th Fleet, operational arm of US Fleet Cyber Command; Lieutenant General Stephen Davis, inspector general of the Department of the Air Force; and Retired Colonel Jen Easterly, now director and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA).

Garret Graff, contributing editor with Wired, moderated the panel that brought the quartet together again. “We are diving back into some of the early history of cyber security and about these four people and their role helping to found US Cyber Command,” he said.

In the mid-2000s, prior to the formation of US Cyber Command, the military, much like other elements of the country, was still getting its arms around the potential risks of cyberspace and the damage bad actors could cause.

Graff kicked off the discussion asking Nakasone about an inciting incident woven into the US Cyber Command’s founding had to do with an infected flash drive in Afghanistan and Operation Buckshot Yankee -- the defense used against the malware attack that resulted.

“I think it’s an important story,” Nakasone said. “It’s 2008, and the Department of Defense realizes that there is malware on both their unclassified and classified networks. These are the warfighting networks that we’re using for US Central Command.”

Three important elements came from this discovery, he said.

First was the jarring impact on the department. “Not necessarily for the unclassified network, but truly, our classified networks have been penetrated,” Nakasone said.

Second, during this incident, he said, the NSA was able to detect and mitigate. “The ideas that Keith Alexander starts to have in terms of, where do we need to go as a Department of Defense with cyber forces, starts to take place,” Nakasone said, referencing the first commander of US Cyber Command.

The third element was the reason for US Cyber Command, he said. “Everything starts to accelerate after the mitigation is done and we start talking about what do we do about this going forward?”

Coping with the malware, and the incident as a whole, proved daunting at first. “It was trying to understand the scope of the problem,” Nakasone said. “It was very, very senior people asking very, very basic questions like, ‘How many computers were impacted?’ Or ‘Where did it come from? Or ‘What do we do about it?’”

The questions would also expose deeper concerns. “It was also, ‘How many computers do we actually have?’” Davis added. “And we could not answer the question of how many computers were on this SIPRNet [Secret Internet Protocol Router Network].” He was referring to the networks used by the Department of State and the Department of Defense for info sharing and communication deemed secret. “There were those basic questions and I think there was a realization that we didn’t really understand the system as well as we should,” Davis said.

The scope, potential ramifications, and apparent obviousness of the vulnerabilities soon hit home. “This was a ‘No Shitter,’” White said. “Everyone wakes up relying on this network -- four stars, senior civilians, commanders rely on these networks to do every bit of all the business of the mission.”

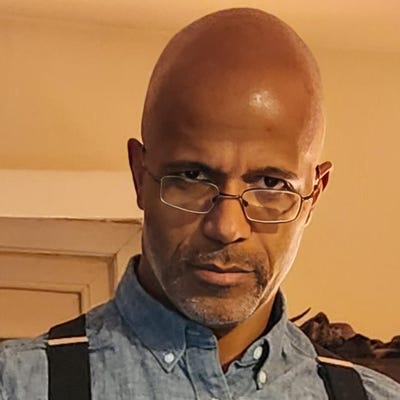

Retired Vice Admiral Timothy White recalls how joint services brainstorming led to plans for the US Cyber Command. Photo by Joao-Pierre S. Ruth

Another major component that played a role in the creation of the US Cyber Command, Graff said, happened in Iraq where Easterly once operated.

“Folks will remember the period of violence in ’06-’07,” she said, “where insurgents -- part of Al-Qaeda in Iraq -- were using the improvised explosive devices and explosively formed penetrators that had catastrophic impact on our troops on the ground and Iraqi civilians.” The head of NSA at the time was General Keith Alexander, who had further plans for the agency’s involvement in the conflict.

“As I recall, he really wanted to take NSA from behind the green door and make us relevant to the warfighter,” Easterly said. “So, we started deploying a lot of NSA officers, whether it was military or civilian, into the field to support the brigade combat teams with cryptologic support teams.”

Team members were also asked to stand up a capability called RT10 -- later RT-RG, Real-Time Regional Gateway -- that was classified at the time, she said. “What it was supposed to do was to take all of the communications in theater that insurgents were using, in particular to plan and operationalize these attacks, whether that’s satellite, or cell phone, or reporting from troops on the ground, and integrate them, and enrich them, and correlate them so we could illuminate terrorist networks not in days or weeks, but in hours and minutes.”

Lieutenant General Stephen Davis, inspector general of the Department of the Air Force, and Jen Easterly, director and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. Photo by Joao-Pierre S. Ruth

Easterly said the project took an incredible degree of entrepreneurialism, innovation, and teamwork, which sparked energy around supporting ground forces and the Joint Special Operations Command to take thousands of insurgents off the battlefield. The success of that made it clear to General David Petraeus, who was in command of Multi-National Force -- Iraq at the time, how important cyber and communications were becoming, she said.

The collective lessons and expertise that developed from such operations were eventually distilled by a small team, White said, who presented their brainstormed plans to General Alexander. “Fifteen months later is the establishment ceremony for the US Cyber Command,” White said.

The joint group that eventually assembled, the proverbial Four Horseman, had convinced Alexander to act on the notion. “It was a small group in his office,” White said. “It was a conversation, and then it became an opportunity to think about a vision. And then it was a discussion about, ‘What do you think?’ And then it was an invitation to see the future.”

About the Author

You May Also Like