Is finding a new job among your resolutions for 2015? Once you have an offer, you need to go -- even if your employer begs you to stay. Here's why.

You're unhappy in your job and don't see that changing, so you update your résumé, revive your network, and start the search process. Two months later, after many stops and starts and a grueling interview process at a top company, you get an offer. You walk into your boss's office and give notice, dreaming about your shorter commute and new, challenging projects.

Then your boss catches you off guard by lobbing a counteroffer.

Your manager swears (cue the violin music) that the company can't survive without you. "You absolutely can't leave! You're too valuable! What do you want? More money? More challenging projects? Work from home? A new title? You got it! We'd do anything to keep you here!"

[What should you get the techie on your list? Read Holiday Gift Guide 2015: What Techies Want.]

Caught up in the emotion, you accept. I see it happen all the time, and this scenario is poised to play out more often as the job market for key tech positions becomes increasingly competitive. Managers, realizing that your slot could remain vacant for months, might offer just about anything to get you to stay.

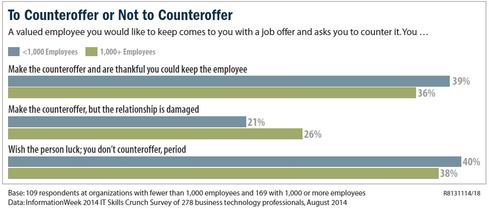

Yet, counteroffers rarely have a happy ending and can even be career suicide. Despite the love and money that is showered upon you during the process, counteroffers change the employee-manager relationship. Something irreversible happens in that room that further erodes an already precarious work situation.

{image 2}

Make no mistake: Your boss will now question your loyalty. You're considered a flight risk. If you had a spot in the inner circle and a role in key decisionmaking, you might no longer be included in those conversations because your boss will no longer trust you. Every time an out-of-office meeting runs long or you have a dentist appointment, your boss will think you're interviewing again. That cloud of suspicion will stay with you.

You can also forget future raises and promotions. Where do you think the money came from to get you to stay? That investment won't be soon forgotten, especially because it was unexpected and so, potentially, had a negative impact on the company.

And, you've used up your most powerful bargaining chip. If it takes the threat of quitting to change what is wrong with your current role, what about the next time? What will you do to top that?

Finally, by accepting the counteroffer, you most likely burn your bridges with the new company -- remember the one that spent all that time on you during the interview process? That team chose you. Now they're back at square one and probably feel like chumps.

From a manager's perspective, counteroffers are a panic move. The offer is (almost) never as genuine as it seems on the surface. In fact, the dirty little secret of the counteroffer is that -- despite how thickly the manager lays it on about how indispensable you are -- counteroffers are not about you. Typically, they're a way to buy time, help the manager save face, or salvage a project. Your resignation might reflect badly on the manager (she can't keep her team together). Or, if there is a big project in process, it will be virtually impossible to meet deadlines without you while also conducting a candidate search on the side.

I have also seen companies use counteroffers as a stall tactic. They make the offer with no intention of paying you that salary for more than a few months. You stay on while your manager discreetly searches for your replacement. Managers generally are operating in crisis mode when they make counteroffers. Beware.

Even if the offer was initially sincere, a few weeks or months later, managers often get a bad case of buyer's remorse. He might resent that you presented him with an ultimatum and regret his decision to counter offer. On reflection, a manager might feel you don't, in fact, deserve that new title or the extra padding in your paycheck.

In fact, well-run, well-managed companies never make counteroffers. They are an ill-advised, reactive business strategy, and company culture and morale often take a hit when one employee is given a counteroffer.

From an employee perspective, more often than not, people who accept counteroffers also become disenchanted with the decision. It puts pressure on them to live up to new, and sometimes unrealistic, expectations. You can't just do the same job for more money and prestige; you have to up your game exponentially. Once the initial high wears off, you're left at the same company with the same problems that drove you to job hunt -- same manager, same culture, same uninspiring projects.

It might be a cliche, but money cannot, in fact, buy happiness, especially on the job. It's been my experience that a vast majority of those who accept counteroffers are gone from the company -- one way or another -- within a year.

The good news is that counteroffers can be avoided.

Employers can prevent this situation by staying close to their people. Encourage managers to have frequent conversations with employees about sensitive but important topics: compensation, titles, and projects. If managers get to the point of a counteroffer, it is too late.

Employees shouldn't shy away from initiating difficult conversations about what they need to stay engaged on the job. If you're unhappy with some aspect of your position but still like working at your company, speak with your manager before embarking on a time-consuming job search. Many employees erroneously believe they need another job offer as a bargaining chip or safety net, but most managers will try to work with employees to fix what they can. They would rather keep current employees happy than go through the expense of finding and training replacements.

Work up the courage to have those conversations. Too often, I hear managers say, "If only I'd known!"

If your manager can't fix the most important issues, then it is time to start the job search process. Once you accept a new job, don't look back. Giving notice can be an emotional experience, especially if your manager presents a sweet counteroffer wrapped in pleas and compliments. However, more money and a new title likely won't fix the problems that led you to seek a new job in the first place. Don't accept that counteroffer. Go forward to advance your career.

Employers see a talent shortage. Job hunters see a broken hiring process. In the rush to complete projects, the industry risks rushing to an IT talent failure. Get the Talent Shortage Debate issue of InformationWeek today.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like