There's not a business in existence today whose operations don't rely on the Network Time Protocol (NTP). Harlan Stenn is the chief maintainer of NTP. In the past year, security researchers have raised a number of concerns about the protocol, which Stenn is addressing even as he prepares a move of half the NTP infrastructure. Here's why it matters.

9 Reasons To Crowdsource Data Science Projects

9 Reasons To Crowdsource Data Science Projects (Click image for larger view and slideshow.)

Imagine trying to relocate half of your infrastructure while simultaneously addressing a series of security issues that are dogging your code. Now, imagine doing all this for one of the most important underpinnings of everything -- every single thing -- on the Internet, and with limited financial resources to boot.

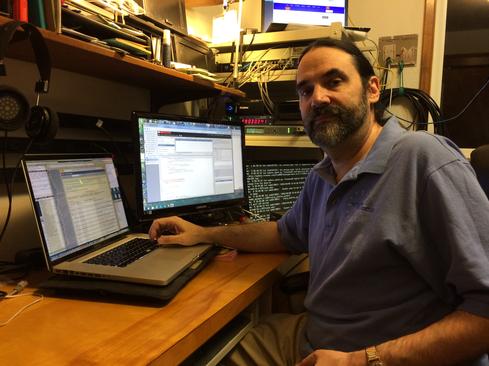

That's where things stand for Harlan Stenn, the chief maintainer of the Network Time Protocol (NTP), known to some as Father Time. NTP is not something you think about every day, but it is essential to the operation of the Internet itself.

NTP is the reliable, but aging, open source code that guides distributed computer systems in their use of synchronized time. Its healthy operation is essential to coordinating servers on the Internet. It establishes a tier of NTP reference servers on the Internet that can be called at any time for a precise time check.

[Want to learn more about issues of computer time synchronization? Read NTP's Fate Hinges on 'Father Time.']

What does all that mean in the real world? Well, NTP is used as the legal basis for time stamps by equity, bond, and financial instrument trading systems on Wall Street. It's used to time medical procedures in clinics and hospitals and chemical processes in manufacturing, along with hundreds of other uses. Windows, Linux, and Unix computers all rely on NTP open source code for their system time-coordination with other computers.

Last June, it was Stenn and the NTP maintainers who added a leap second to network time, keeping it in precise alignment with a slightly lengthening solar day.

But NTP has faced a dwindling number of maintainers over its 31-year life span. Original author David Mills retired, then fell blind in his later years. Stenn now works 12 to 15 hours a day on NTP. His commitment to NTP, along with his precarious finances, were highlighted in an InformationWeek article a year ago.

Stenn previously had his own consulting practice as well, but gave that up two years ago to concentrate solely on the care and feeding of NTP. He relies on annual grants from the Linux Foundation, as well as funds raised from the nonprofit Network Time Foundation, which Stenn launched in 2011 and currently operates with Sue Graves, director of client services.

Recently, a series of NTP security issues have popped up as the result of testing by laboratory researchers at Boston University and Cisco. Security testers at both organizations are checking the code for its ability to withstand tampering and intruders.

The issues they found started getting reported early in 2015, Stenn told InformationWeek in an interview in February 2016. On the plus side, no breaches have been reported from actual NTP use in production, at least not publicly, so far.

Four major updates were made to NTP throughout 2015, which addressed a combined total of 20 exposures and security issues, according to Stenn. That's an unusually high number of updates for the protocol in a single year. The four updates also included 100 additional bug fixes and 150 improvements to the protocol. That's a significant amount of activity in a single year.

Still, Stenn said, in some cases what security researchers term an exposure is really what he considers the accepted way NTP is supposed to work. For example, he said, "Cisco researchers said they were concerned about one of our fixes. We did something that would allow an attacker to set the clock backwards."

According to Stenn, NTP users already have the means to set their clocks backward or forward. They're meant to have that power under the protocol to adjust their systems to the correct time.

But security specialists said it could allow an intruder to essentially erase time in a system log and cover up his tracks of activity. Stenn argued that if system administrators watch their alerts from NTP, they'll know when the time on their server has been adjusted and can make sure they did it. Ultimately, though, Stenn ended up eliminating the identified issue.

"Security issues have been taking up half ... no, three-quarters of my time since September," Stenn said. That's something new in a schedule already filled with maintenance issues for the protocol, which must be kept running smoothly across many versions of Linux, Windows, and Unix.

Stenn said there's no single cause for the spate of security issues, other than an increasing nervousness in general over the state of the open source code that enterprise and public Internet operations depend on, he said.

NTP Security Tests: Natural Next Step

At Boston University, associate professor of computer science Sharon Goldberg said NTP is so fundamental to the operation of computers on the Internet that examining it became an extension of her group's previous work. "My research lab is interested in the security of core Internet protocols like [Border Gateway Protocol] and [Domain Name System]. Studying the security of NTP is a natural next step for us," she said in an email message to InformationWeek.

Goldberg and three of her lab researchers have brought six issues to Stenn's attention. The Cisco team spotlighted an additional fourteen. At press time, the Cisco researchers were unavailable for comment.

"We were hoping to close out a series of security issues in December, then Cisco came along and said, 'Oh, here's eight more,'" said Stenn, leading him to work on painstaking security patches even as other concerns loomed.

One issue that Stenn admitted deserves more of his attention: a replacement of the Autokey token, which is used to authenticate an NTP server to a client. When first developed in the 1990s, Autokey was a good way to provide a trusted token between the server and the client, assuring the recipient that the time stamp came from a trusted source. Now that token can be broken in 30 minutes on a laptop, Autokey users are advised to throw out their tokens after that amount of time and get another.

The new functionality is being worked through a separate project, Network Time Security. When finished, it will be adopted as an extension to NTP itself. The work is being led by Richard Welty, a lecturer in the College of Engineering and Applied Sciences of the State University of New York at Albany.

But Stenn said that work cannot proceed in a vacuum. NTP project volunteer Danny Mayer, Network Time Foundation's Graves, and Stenn -- along with two to three other developers -- participate "on a weekly call" with Welty, discussing approaches and simpler ways to accomplish what they're trying to do.

The NT Security code will be meshed back into NTP when it's ready. "We were hoping to have it done six months ago," said Stenn. "A year ago, a couple of companies told us, 'We'd like this to happen sooner...'"

In November 2015, phase 1 of NT Security was completed. It's already progressed to phase 12, with many design improvements since last fall, but no date in sight for version 1 to be ready.

Moving Time

At the same time as the security issues are being raised, Stenn faces a looming deadline. Half of the NTP's physical infrastructure, currently housed in Redwood City, Calif., must be shut down and moved to new locations, all without disrupting NTP's operation.

For the past 15 years, nonprofit Internet Systems Consortium (ISC), keeper of the Domain Name System (DNS) and its BIND system, has been hosting multiple open source projects, including, at no charge, half of the NTP infrastructure in the back of its building in Redwood City, Calif. Servers, switches, routers, and GPS gear are among the items housed there. The Internet Archive is also among the open source projects that have been hosted by ISC.

Brian Reid, operations manager at the ISC, said in an interview with InformationWeek that the organization spends 2.5 times as much as "the big boys" (professional hosting companies) to sustain NTP's equipment and that of a dozen other projects.

(Image: deepblue4you/iStockphoto)

A year ago, ISC notified all the open source projects it was hosting that they would have to move. "We found we were spending hundreds of thousands [of dollars] a month to keep the projects running," Reid said in an interview. "We enjoyed doing it over many years, but the electricity costs twice as much as when we started... money isn't as available as it used to be."

Stenn acknowledged the debt NTP owes ISC for its free hosting, an effort he said amounted to about $2,000 worth of free space, power, and cooling per month.

The NTP equipment running at ISC's facility includes two switches; two firewalls; four Web servers; two dozen additional servers that handle email, development, and protocol hosting; and several application servers. There are also two GPS receiver "cones" on the roof that perform a needed radio-to-digital conversion for checks with atomic clocks on GPS satellites.

It's a rack full of equipment representing over half of NTP's infrastructure. The rest is in two other locations: a data center at Oregon State University in Corvallis and a colocation service, Hurricane Electric, in Fremont, Calif.

Stenn has found sites for the soon-to-be displaced gear at a hosting service in Boston and a colocation provider in Chicago. He said he wants to execute the move by late spring. At some point, the urgency of the pending move will have to override the other demands on his time, he said.

It's unclear how much the move itself will cost. But there's one big catch: There's no budget set aside for an NTP move. The existing equipment can't be unplugged and shipped to the new locations without at least some new switches and servers being purchased and put in place for the cutover. During the move, the Network Time Protocol must keep running at all times, he pointed out.

Stenn said so far he's received an additional $2,000 from the Linux Foundation (www.linuxfund.org, an open source fund raiser independent of the Linux Foundation) toward equipment purchases. However, the annual $84,000 grant he gets from the organization is restricted to use for NTP development and maintenance work. It can't be used to purchase new equipment needed for a switch-over to a new location, according to Stenn.

Stenn cited many claims on his attention, including the need to come up with a standard specification, a description in precise English language for what NTP does, but he keeps coming back to the need to pay attention to both security fixes and the upcoming move.

Executing an uninterrupted cutover to new facilities is a task that makes him nervous. "It's not like we can grab a suitcase and throw a few clothes in it and move. It's a huge thing."

Instead of preparing for it, he's combating security researcher worries about NTP. "We've been kind of burning one end of the candle faster than the other," he said.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like