Avoiding audits and vendor fines isn't enough. Take control of licensing to exact deeper software discounts and match purchasing to actual employee needs.

Get the entire Sept. 2 issue of InformationWeek - no registration required.

Get the entire Sept. 2 issue of InformationWeek - no registration required.

Look at the software in your organization in three ways: software you've purchased, software you've installed, and software that employees actually use. These are three distinct lists that can get surprisingly out of sync, and it's never good when that happens.

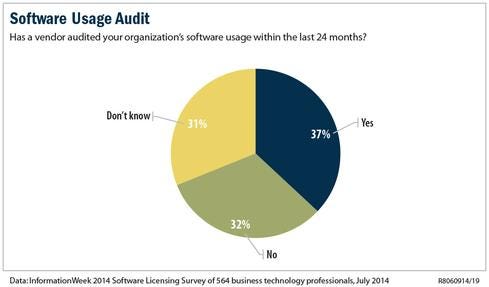

When software installs exceed licenses, you're out of compliance and could lose discounts and face steep "true up" fees or fines if the vendor finds out via an audit. Make that when a discrepancy is uncovered in an audit. Our InformationWeek 2014 Software Licensing Survey, completed in July, reveals that more than a third, 37%, of organizations have been audited within the last 24 months. The percentage is even higher, 40%, for companies with 500 or more employees, and separate research shows that large companies can expect six- to seven-figure fines when there are big discrepancies.

It's surprisingly easy for installs and licenses to get out of sync because enterprise software vendors, including IBM, Microsoft, Oracle, and SAP, make it easy for your employees to download software without paying for it. Vendors of enterprise software seldom lock it up with the kind of license keys used to control consumer software installs. Complicating matters are licensing terms related to virtualization, per-CPU, or business roles that confound even experienced buyers and administrators.

Figure 2:

Even worse than getting caught on the wrong side of an audit is paying too much for software straight away. This happens when companies license software but never install it -- the dreaded shelfware. In other cases, companies license and install software that employees never use, yet they have no way of knowing it because they can't track usage. A third form of waste is emerging as more tech buying -- particularly for cloud-based software -- moves outside the IT organization. When 12 different sales and marketing types are buying SaaS-based CRM seats on their credit cards, it's impossible to get the enterprise-scale discounts your organization deserves.

The larger and more distributed the company, the harder it is to keep track of software licenses, installs, and usage. Even without the added complexity of virtualization, SaaS, and hybrid cloud environments, you're kidding yourself if you think you can manage licensing using spreadsheets and paper records.

IT asset management systems and software license optimization software go a long way toward getting software license entitlements, installs, and usage into sync. But tech won't cure all ills. Company leaders must forge a clear buying strategy that balances centralized control and the vendor bargaining leverage that comes with it with the need for departments to get exactly the right software for the job when they need it. Doing so requires IT, purchasing, and business unit leaders to work together. Finally, there's shadow IT. You must educate line-of-business leaders and IT administrators about the consequences of rogue purchasing, unauthorized installs, and changing usage patterns sparked by rising use of mobile devices.

Audits Strike Fear

Let's start with the understanding that software is incredibly valuable and that vendors spend lots of money to develop software functionality. They deserve every penny that's due to them under their stated licensing terms. OK, that doesn't lessen the frustration IT leaders feel when hit with a surprise million-dollar bill after an audit turns up software they didn't know they had installed. But a vendor audit gone sour provides the impetus to improve software license management.

The right to audit is spelled out in the fine print of software contracts, and research points to rising vendor audit activity. The audit compares the software that customers have installed with what they are licensed and entitled to use. If a vendor isn't satisfied with a company's response to an initial inquiry, it has the right to run scripts on that customer's network that will uncover where its software is installed and in use.

Audits rarely turn out in the customer's favor. The average audit true-up cost for companies with about $50 million in annual revenue is $263,000, according to the 2013-14 Key Trends in Software Pricing & Licensing Survey, the latest annual report published by software license optimization vendor Flexera with input from IDC. For companies with about $4 billion in revenue, the average audit true-up cost is $1.6 million.

Apparently, a better than one-in-three chance of an audit and the prospect of a six- to seven-figure fine isn't enough to motivate many companies to take control of license management.

"I've talked to some CIOs who say, 'I don't know what my risk is of being audited, and I don't know that if I'm audited I'll be out of compliance,'" says Amy Mizoras Konary, research VP, software licensing and provisioning, at IDC and a collaborator on Flexera's annual survey. "The attitude is 'I would rather take the risk of being audited than pay to fix a problem that we might not have.' But companies that take this approach are typically rewarded with audits." (See related story, "5 Signs You'll Face A Software Audit.")

Tools Of The Trade

IT's first line of insight (and audit defense) is usually IT asset management software. BMC, CA, Hewlett-Packard, IBM, Symantec, and other vendors provide general-purpose systems that correlate inventories of software and other IT assets to contracts, licenses, and equipment leases. This software is typically aimed at improving IT operations -- providing tools to detect failures across servers, storage, networking devices, software suites, and personal computers. At best, this software might discover and inventory what software is installed on which devices, but it doesn't analyze software usage and compare that with usage rights to give companies some idea if they're spending their money wisely.

In some cases, software vendors offer free tools geared toward deploying their products according to their licensing approaches. Microsoft, for instance, offers the Microsoft Systems Center Configuration Manager (SCCM), which provides remote desktop and server control, patch management, software distribution, operating system deployment, network access protection, and hardware and software inventory. IBM often requires customers to use its License Metric Tool as a way to determine how many PVUs (processor value units, an IBM licensing metric) are in use.

The trouble with vendor tools is that they don't capture every metric and deployment variable needed to manage licensing, says IDC's Konary. What's more, these tools help you with software only from one vendor, whereas

even midsize companies invariably manage hundreds of software titles. "You'll get one version of the truth out of each tool, but companies have to bridge the gaps between those tools," Konary says.

Most companies try to bridge those gaps using spreadsheets and paper, but IT organizations are warming to third-party license management and license-optimization software as audit activity increases. The license management systems start with discovery tools that promise to spot all installed software, and with inventory tools for compiling and tracking all licenses. They also compile usage information so that companies can begin to assess licensing levels. Vendors in this camp include 1E, Express Metrix, and Snow Software.

Sophisticated license-optimization systems analyze exact license terms and entitlements, relying on libraries of vendor-specific SKUs (stock-keeping units) and usage rights. By knowing how employees are using software versus the various usage rights, companies might be able to downgrade or eliminate some licenses. Vendors in this camp include Aspera Technologies and Flexera Software.

License management and license-optimization software vendors aren't always as transparent about their own prices, however. Aspera and Flexera declined to disclose pricing. Express Metrix puts the price of its license management software at $5 to $15 per seat, depending on volumes. If a $50 million company can buy 500 seats at $15 per seat, that's just $7,500. And if a $4 billion company can buy 20,000 seats at $5 per seat, that's $100,000. That's not even close to those $263,000 and $1.6 million true-up fines that companies of this size typically face. Keep in mind, though, that more sophisticated optimization software costs more.

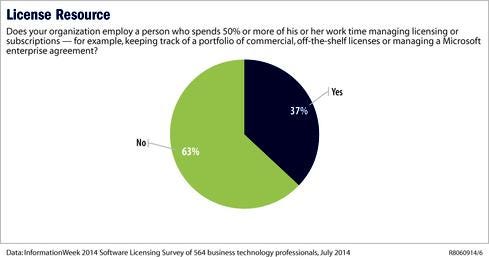

Figure 3:

Software alone can't solve your licensing challenges, so you should also consider the cost of training a current employee or hiring an experienced full-time employee to focus on managing software licenses. According to our 2014 Software Licensing Survey, which had 564 respondents, 37% of companies employ a person who spends half or more of his or her work time managing licensing and subscriptions.

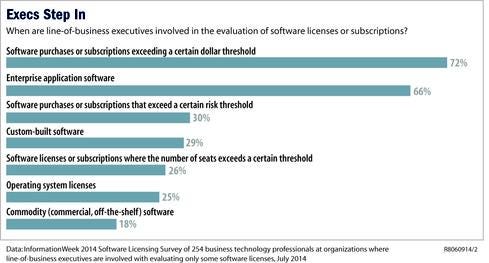

Whether these managers are part time or full time, they should be among the leaders of a company-wide effort to develop processes, policies, and training programs around software licensing. Our survey finds that lines of collaboration already exist, with more than half of respondents reporting that C-level executives and purchasing departments (each at 52%) are involved in decisions about software contracts, licenses, and subscriptions. Line-of-business executives also get involved in licensing, but this happens mostly when software purchases exceed certain dollar thresholds (72%) or involve enterprise software (66%).

How To Get A Grip

Eighteen months ago, Hearst Corp. hired Shawn Bennett for the full-time position of executive director, IT procurement, to take control of software spending. He had played a similar role at Liberty Mutual, a $38 billion insurance company. His goal is simple: "purchasing more software for less money." Bennett looks to do that by not just tracking software purchases and installations, but also by analyzing usage and entitlements to optimize software spending and get better deals by leveraging Hearst's purchasing power.

Hearst, a company with 20,000 employees and $4 billion in revenue, had master purchasing agreements for popular Microsoft and Adobe products. But with offices for 20 newspapers and more than 20 TV and radio stations, Hearst suspected that employees were buying locally without tracking installs and usage and without taking advantage of or contributing to corporate discounts.

"Everybody knows, somewhere in filing cabinets, what was purchased, but the first thing you need to do is find out what you actually have out there," says Bennett, who went through a formal RFP process before subscribing to Flexera's cloud-based software license-optimization applications about a year ago. "To bring all that together in one system was a huge value to us."

Figure 4:

Bennett knew Hearst's biggest software spend (and risk) included Microsoft desktop and server products, as well as Adobe software used by the company's print newspaper/magazine and TV businesses. Both vendors are known for frequent auditing.

Flexera's FlexNet application took install data from Hearst's IT asset management tools, including Microsoft's SCCM and Symantec's Altiris client management suite. For software not tracked by vendor-specific or third-party tools, Flexera also has a discovery application that identifies what's installed on desktops and servers. "Within a few weeks I was able to plug existing tooling into the system, and I had clear visibility into what we have installed," Bennett says.

Answering a seemingly simple question like, "How much Microsoft Office do we have installed?" would previously have taken weeks, Bennett says, because the information had to be pulled from 20 places and aggregated. "Now I can push a button and I'm able to answer that question with confidence," he says.

Like other IT asset management tools, Microsoft's SCCM discovers what's installed on each machine, but these details are buried in complex reports that aren't geared to quickly answering the big questions in audit scenarios, Bennett says. FlexNet delivers an aggregated view formatted for license compliance and software optimization.

Go On Offense

Getting a handle on software installs is just a first step. Next, Hearst uploaded all of its software purchasing information into FlexNet so it could compare licenses to installs and get a sense of the company's compliance position for each software title. "It sounds simple, but it was a pretty monumental task pulling together all the historical purchase records from various filing cabinets and locations throughout the company," Bennett says.

Figure 5:

Hearst chose Flexera in large part because it has vendor SKU and product-use rights libraries, covering more than 14,000 vendors. "The software reads the SKU information, and with that it knows how that product is licensed, including whether there are upgrade or downgrade rights," he says.

The final step, comparing software usage to licenses and usage rights, combats shelfware. If a company finds that software allocated to

specific users hasn't been used in the last 60 or 90 days (or whatever threshold a company chooses), it can uninstall that software and eliminate that license or reallocate it to another user.

Hearst is in the early stages of its optimization efforts, but Bennett says it already has reallocated more than 1,000 Adobe and Microsoft licenses that weren't being used. Let's say that's a corporate-discounted license for Adobe Acrobat or Microsoft Office that might have otherwise set Hearst back $75 to $125 a seat. That's $75,000 to $125,000 in savings on those titles alone.

Bring On Complexity

Software optimization doesn't always involve a binary, buy-another-license-or-not scenario. For sophisticated enterprise applications such as business intelligence, CRM, and ERP, usage analysis might reveal that specific employees can be downgraded to less-expensive licenses. In simple cases, that choice might be "read-only," "contributor," or "power user" licenses. SAP, for one, has more than 60 different user categories across its Business Suite licensing schemes.

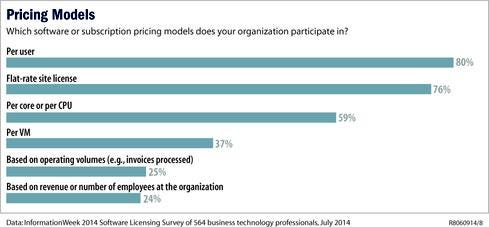

Server-based licensing schemes and virtualization, as well as private and public cloud schemes, have introduced yet more complexity (see related story, "Cloud Won't Cure Licensing Woes"). The majority (55%) of the respondents to our survey say they prefer flat-rate site licenses, but they often have to deal with per-user, per-CPU, per-core, or even per-VM licensing approaches. IBM came up with its PVU metric in response to virtualization -- meaning it charges based on how many processors the software runs on, not on how many chips (which might hold multiple processors) or servers. Licensing levels can quickly change depending on variables that aren't fully captured in the IBM License Metric Tool, says Christof Beaupoil, co-founder and president of Aspera Technologies.

IBM's DB2 database, for example, might be free when provided as part of another product, but IBM will likely charge for it if it's used with anything other than the product with which it was bundled. "If an audit reveals that a third-party product is connected to the database, guess what: It has to be licensed," Beaupoil says.

It's often the case that software is initially installed and used in accordance with licenses, but access and usage patterns evolve over time, getting out of sync with the original terms and usage entitlements. "Every time you have a change in how software is being used, the software vendors realign how they license their software, so customers have to reassess how they capture and count licenses," Beaupoil says.

Figure 6:

With client computing, for example, we've gone from having desktops to having desktops, notebooks, tablets, and smartphones, as well as virtual desktops. Employees access software in the cloud, and they're allowed to bring their own devices to work. On the server side, licensing has evolved from mainframes to servers to multi-CPU and multi-core servers to today's virtualized and private cloud deployments.

Evolve Your Approach

Software management and optimization tools give companies comprehensive information on installs and usage that they can compare to licenses, but software alone won't solve the license management problem. Business leaders, IT teams, and purchasing departments must team up to ensure that their good intentions don't backfire. Purchasing departments, for example, are known to strike special deals that can't possibly be enforced by IT. "We're seeing more usage-based licensing, with pay-per-use or concurrent-user approaches," says IDC's Konary, "but IT could tell them that there are typically no tools available to track and meter usage and ensure that they're not exceeding that limit."

Another licensing gotcha is what Konary calls the "honor system" approach, which makes it all too easy for administrators to install and turn on features not covered by a current license. Software vendors defend this approach, arguing that it makes it easy for customers to obtain software and try new features. But it also creates the distinct possibility of using features that haven't been paid for. And audits uncover those discrepancies. When that happens, true-up fees might apply whereby companies lose discounts and face full list prices applied retroactively.

Oracle is the leading practitioner of the honor system approach. Most software vendors have switched to what Konary calls a "trust-but-verify" approach, whereby customers who download software or try to turn on optional features will get pop-up messages that say something like, "You don't have access to this feature. Call your sales representative and we'll turn it on for you."

License management teams should create policies and education programs around key software titles known for tricky licensing and frequent compliance problems. "Oracle Database, as an example, is not friendly within virtualized environments," Konary says. "A simple rule might be, 'Oracle Database does not go into virtualized environments, and if it does, here are the steps that must be followed.'"

Microsoft Office is another source of frequent compliance problems because it's difficult to track decentralized desktop software and reconcile usage with complex licensing terms. All the more reason for clear processes and policies around buying software, choosing licensing levels, installing and handling upgrades, and transferring licenses that aren't in use.

First Things First

Audits are bad enough, but when companies aren't prepared for them or they don't go well, they can turn into time- and energy-sapping disputes. Seventeen percent of our survey respondents said their organizations have had at least one contract or usage-rights dispute with a vendor over the past two years. To avoid this scenario, start your software compliance and optimization efforts with the titles that represent most of your spend and your biggest audit risk.

The five vendors most likely to audit corporate software licenses are Microsoft, Adobe, Autodesk, Oracle, and SAP, in that order, according to a 2013 survey by Express Metrix. Among customer organizations with 10,000 or more employees, IBM jumped to the No. 4 spot, bumping the others down one spot. Rounding out the survey's seventh to 10th most-frequent auditors are McAfee, Attachmate, VMware, and Symantec.

Don't be content to just make sure licenses are in line with installations. Do a discount double check to try to lower your bill. Eighty-eight percent of the respondents to our survey say they have negotiated discounts of more than 5%; nearly half (47%) say they've negotiated discounts of 11% to 20%. With centralized knowledge of all purchasing (even if decentralized units still do some of the buying), you'll be able to take advantage of every discount available.

With that victory, push to the next level of sophistication by acquiring a deeper understanding of how employees use software so that you can optimize purchasing. Maybe you're buying expensive power-user licenses for casual users, or maybe those casual users aren't really using the software at all. With knowledge of usage and entitlements, you'll be able to choose the right license levels for each user. And like Bennett of Hearst, maybe you'll be able to reallocate unused licenses and save tens of thousands -- if not hundreds of thousands -- of dollars by avoiding unnecessary purchases. You still won't be thrilled when the software auditor knocks on your door. But you'll be ready.

Related stories:

5 Signs You'll Face A Software Audit

Cloud Won't Cure Licensing Woes

Get the entire Sept. 2 issue of InformationWeek - no registration required.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like