Employees resisting social business? You can improve adoption by predicting how these types will react to new ideas.

Has this happened to your company? You introduce a social business platform to great fanfare. You advertise and promote internally, maybe even sponsoring games and scavenger hunts with the hopes of getting your employees excited about using it.

At first everything seems to be going great, but eventually usage stalls -- maybe even deteriorates -- and you never reach that critical mass of employee adoption that provides the business benefit you were looking for.

There's a good chance that scholar Everett Rogers and technology consultant Geoffrey Moore could have predicted this situation years ago. In the early 1960s, Rogers developed a theory called the Diffusion of Innovations. If you've ever used the term early adopter, you may have been talking about this theory without even realizing it. The theory focuses on understanding the factors that can accelerate or inhibit the spread and adoption of a new idea within a community or organization.

[ Want more tips? Read Social Business Adoption: Focus On People. ]

I'm certainly not the first one to make the connection between diffusion of innovations and social business adoption, but I hope to present some simple, practical steps you can take to improve employee adoption of social business tools and processes. For more on this concept, read Rogers' book, Diffusion of Innovations (Free Press, 2003).

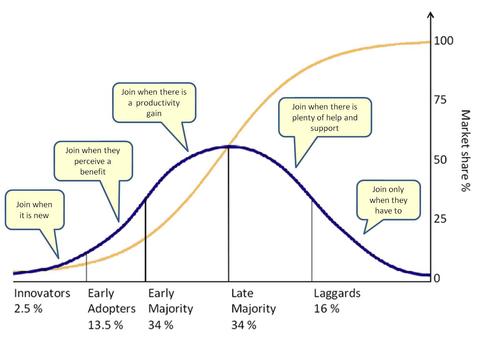

According to Rogers, not everyone has the same motivation for adopting a new idea. He identifies the following five types of adopters:

Innovators adopt something simply because it is new. They love exploring for the sake of exploring and are willing to take risks, even if those risks result in failure.

Early adopters are often opinion leaders. They are similar to innovators in how quickly they adopt, but they are more concerned about the coolness factor and maintaining their reputations as being ahead of the curve on new ideas.

Early majority and late majority are the critical mass that ensures adoption. The early majority looks for productivity and practical benefits more than coolness or reputation. The late majority is similar but also expects a lot of help and support before they are willing to commit.

Laggards, as the term implies, are slow to adopt. They are the most resistant to change and do so only when forced to adopt because everyone else has.

About 30 years after Rogers completed his research, Geoffrey Moore wrote Crossing the Chasm. While the book focuses on how the diffusion-of-innovations theory can be used for marketing high-tech products to customers, many of its ideas can be applied to the internal adoption of social business. In fact, I think Moore's "chasm" is the crux of many social business failures. The chasm he describes is the gap between the early adopters and the early majority.

It's easy to see how to use innovators to attract early adopters, and the same goes for using the early majority to attract the late majority. These adjacent types are relatively similar to each other. Of course, the laggards will come around eventually, if only because of the shift in cultural momentum.

But that pesky gap between the early adopters and the early majority is the real killer. How do you take something that's attracting users because it's new and cool, and reframe it so that it attracts users because it's useful and valuable -- especially if the real value comes from fundamental behavior change, not just tool adoption? What if playing up the fun, cool aspect might actually be detrimental to attracting employees who are pragmatic and practical?

In my next article I'll discuss what steps the theory recommends to facilitate adoption and describe a streamlined model I've used in my own company to help you understand when and where to shift your focus as you progress along the adoption curve.

Among nearly 900 qualified respondents to our 2013 Mobile Commerce Survey, 71 percent say m-commerce is very or extremely important to the future of their organizations. However, just 26 percent have comprehensive strategies in place now. That spells opportunity. Find out more in the 2013 Mobile Commerce Survey report. (Free registration required.)

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like