The Observer: The Bliss Of Consistency

It's time to break down the stubborn, near-indelible boundaries that still separate the business and IT sides of the house and keep good data from losing its way, says Lou Bertin.

"Most enterprises don't fathom the magnitude of the impact that data-quality problems can have." Thus wrote Ted Friedman, principal analyst with Gartner, as reported recently in the InformationWeek Daily and in "More Focus On Bad Data".

According to his research, a quarter of major international companies are working with poor-quality data that is remarkably inaccurate or incomplete. Moreover, Friedman concludes, poor-quality data has become perhaps the leading cause of failure for high-profile and high-cost IT projects.

Ted is constrained by the rock-solid reputation his firm has more than earned over the years for quantifiable research that's backed by impeccable analysis. I'm not. My take: Ted undershoots the mark by, oh, three quarters.

Friedman defines poor-quality data by using several components, ranging from consistency--whether the data is identical when stored in multiple locations--to accuracy and relevance. As well, Friedman's methodology dictates that if there's data but it's not relevant to the process or project at hand, it's worthless.

Bravo, Ted.

Using his methods--which allow for the inevitable presence of corrupted data--how many of you can honestly say that your organizations or enterprises are working with wholly "high-quality," high-value data as you go about your tasks either great or small? Would any but the slightest few brave or foolhardy hands be raised to be counted among the cognoscenti? I thought not.

Even within the highly regulated, utterly reputation-conscious world of financial-services institutions, the inconsistencies can be maddening when online statements don't reconcile with reality. Has anyone ever heard of there being a mistake on a medical insurance form despite the potential penalties attached? Have the IRS or your local motor-vehicles administration ever gotten their internal wires crossed when dealing with your individual accounts?

I concede the point that these are small-potatoes examples, but they serve to prove the thesis Freidman is insightfully putting forth. Of course, banks and exchanges ensure that their daily reconciliations are pluperfect. The penalties for those being otherwise are Draconian and somehow failing to attain daily "perfection" simply isn't an alternative.

But what of the majority of enterprises out there where inaccuracies, inconsistencies, and inevitable conflicts within data sets don't bring down the wrath of regulators. You know, companies and organizations like yours where the penalty is lack of competitiveness or lack of complete customer satisfaction, but nobody loses their jobs and wins jail time.

Business-intelligence technologies and highly evolved, proven techniques for deploying same have been out there for a long time now, but there's one small flaw in the ointment. If the data being filtered, funneled, and otherwise refined by those phenomenally powerful business-intelligence technologies is no good to begin with, how terrific do you suppose the resulting analyses will be?

At a recent InformationWeek roundtable sponsored by a business-intelligence products and services provider, an attendee offered the following eloquent locution. To wit: "What we're looking for is a single point of truth." Perfect, yet seemingly unattainable.

Are there solutions afoot to the problem that's been occupying Friedman and so many of you for so long? Of course, but technology isn't the answer in and of itself. Per Friedman: "If you're only throwing technology at the problem, at best you'll only get short-term, lukewarm benefits."

Per those of you I've spoken with often on the subject over the past year, the ultimate solution will be much tougher to attain in that it involves changing organizational and, worse, individual human behaviors.

That, friends, is the ultimate toughie. It entails breaking down the stubborn, near-indelible boundaries that still separate the business and IT sides of the house. It demands that no organizational entity look upon data in a proprietary fashion. It further requires that someone, somewhere be willing to sign the equivalent of an intramural Sarbanes-Oxley statement as to veracity and verification.

Any volunteers for that one?

And therein lies the dilemma. As another roundtable attendee put it: "Technology is easy to understand, but human nature is impossible to figure." Amen to that. Until we reach the stage where either carrots, sticks, or the prospect of doing the perp walk bring us to understand that there's bliss in consistency, Friedman's going to have lots to write about for a long time to come.

To discuss this column with other readers, please visit Lou Bertin's forum on the Listening Post.

To find out more about Lou Bertin, please visit his page on the Listening Post.

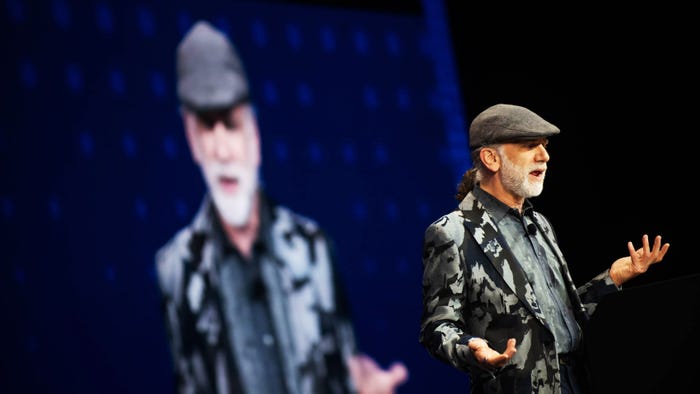

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

How to Amplify DevOps with DevSecOps

May 22, 2024Generative AI: Use Cases and Risks in 2024

May 29, 2024Smart Service Management

June 4, 2024