Apple seems blind to the irony of selling an app that supports free speech when it does not do the same.

Apple approved an app designed to invite expressions of solidarity with Charlie Hebdo, the French satirical magazine attacked by terrorists last week, without recognizing the irony of its endorsement.

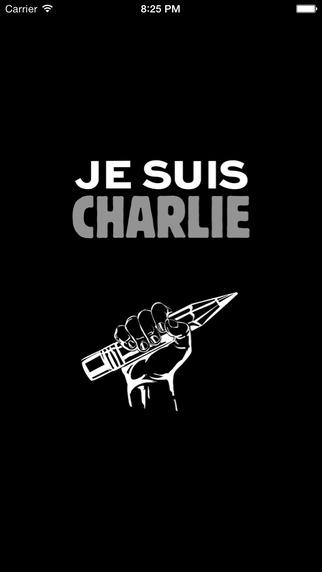

The app, Je Suis Charlie, takes its name from the French� for "I am Charlie," a statement of support for the free expression championed by Charlie Hebdo and opposed by the gunmen who killed 12 people associated with the publication.

According to French newspaper Nice-Matin, the two developers of the app appealed directly to Apple CEO Tim Cook to have the app approved as fast as possible, and Apple agreed, provided Nice-Matin became the app's publisher.

Apple did not immediately respond to a request to confirm reports that CEO Tim Cook personally ordered the app to be fast-tracked. The company's typical review process can take a week or more.

But Apple's approval of the app does not mean Apple approves of Charlie Hebdo's content. The company generally does not allow the publication of the sort of boundary-pushing satire for which Charlie Hebdo is known. Its App Store Review Guidelines forbid it.

Though Apple exempts "professional political satirists and humorists" from its "ban on offensive or mean-spirited commentary," it also refuses to allow "apps containing references or commentary about a religious, cultural or ethnic group that are defamatory, offensive, mean-spirited or likely to expose the targeted group to harm or violence."

[Need anti-hacking tips? Read How Not To Be The Next Sony: Defending Against Destructive Attacks.]

Apple is not alone in its commercially motivated caution, but its insistence on approving app content makes it a publisher as much as a technology company.

Publishers should be champions of free expression, but they might shy away from controversy. The New York Times, TIME, CNN, and other respected US new organizations ran stories about this week's issue of Charlie Hebdo without showing its cover depicting the prophet Mohammed, the act of publishing that is anathema to extremists. For this omission, Clemens Wergin, Washington bureau chief for German newspaper Die Welt, suggested the American media had become "a new gold standard of hypocrisy."

Similar fears have UK Prime Minister David Cameron promising to ban encrypted communication tools if re-elected, as if the answer to censorship through terror is to make speech less free.

Apple has become less restrictive toward third-party content under Tim Cook, but it continues to censor, an act it calls "curation." After initially rejecting the game "Papers, Please," which challenges players to be a border guard, Apple allowed it, minus the image of nude body scans that contribute to the game's exploration of security. Developer Lucas Pope appears to have accepted the compromise, and even expressed sympathy for Apple's position as a gatekeeper (which isn't far from the position of the border guard depicted in his game) in an interview with Ars Technica.

Apple's treatment of Je Suis Charlie and Papers, Please shows more tolerance for challenging expression than its 2013 removal of Sweatshop from the App Store, and its refusal to approve Drone Strike Alert (2012), an app that notifies users when US drone strikes occurred, or Phone Story (2011), about the ethics of smartphone manufacturing. But the company falls short of the sentiment expressed through "Je Suis Charlie."

Charlie Hebdo is not afraid of free speech or of offending. Those made timid by commercial concerns, the political climate, or excessive deference are not Charlie Hebdo.

Apply now for the 2015 InformationWeek Elite 100, which recognizes the most innovative users of technology to advance a company's business goals. Winners will be recognized at the InformationWeek Conference, April 27-28, 2015, at the Mandalay Bay in Las Vegas. Application period ends Jan. 16, 2015.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like