California’s New Deepfake Laws Await Test of Enforcement

An effort to quell misinformation that could cloud the US presidential election may come down to compliance among companies that publish and share content.

On Tuesday, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed into law policies meant to halt the creation and spread of GenAI deepfakes during the tense 2024 election, as well as other legislation. The new laws to prohibit deepfakes, as well as other potential misinformation harms, put X (formerly Twitter) and other large social networks on notice. The new policy bans the creation and publishing of election-themed deepfakes for 120 days in advance of Election Day. It also prohibits election deepfakes for the immediate 60 days that follow.

In a statement, Newsom touted the law as a means to protect democracy and election integrity. This comes after Elon Musk, owner of X and self-proclaimed champion of free speech, previously shared a deepfake video of presidential candidate and current Vice President Kamala Harris that made it appear as if she disparaged her own qualifications. While Musk may have claimed the audience knew it was a joke, Newsom’s policy aims to prevent such fake messages from seeing the light of day. How California’s legal stance on deepfakes affects boardrooms and courtrooms might not be cut and dry.

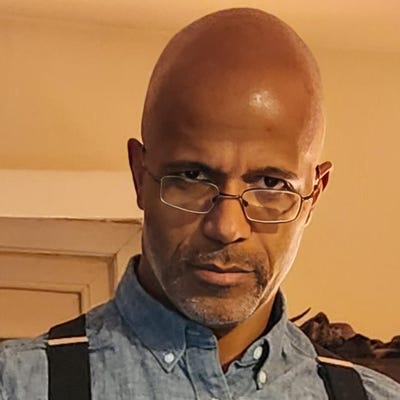

“The thing that keeps coming to my mind is just the complexity of what they’re trying to do,” says Perry Carpenter, chief human risk management strategist with KnowBe4. “Maybe their hearts in the right place, but I don’t know that this round of legislation is going to have the efficacy they want to have.” Carpenter is also the author of “FAIK: A Practical Guide to Living in a World of Deepfakes, Disinformation, and AI-Generated Deceptions.”

The law prohibiting election-themed deepfakes is already in effect and Carpenter is curious to see how it plays out in the real world. “If we want to say that this legislation is successful in some way is that it’s forcing discussions, and I think that’s really, really important.”

Part of the problem with deepfakes is how easy it is to create them thanks to generative AI, even with limited technical skills, he says, citing research he conducted for his book. For the moment, the technology to generate deepfakes is not evenly distributed. Should the day come of its ubiquity in availability in a few years, Carpenter says life could become quite difficult to navigate.

“The technology is here, just not everybody knows about it yet,” he says. “People know that it’s really easy to create a voice clone. It’s really easy to create a deceptive image and sometimes even easy to create deceptive video.” Though technologists understand this, Carpenter says society itself is still largely under the impression that deepfakes are not effective in duping people -- that there is always some sort of “tell” that can identify a deepfake.

However, even with advance warning of bogus, fabricated content, he says only about 21.3% of the time are people able to pick out the deepfake, with about the same percentage misattributing that content. “Which means that we’ve already hit this crossover point where people don’t know what’s real and what’s not,” Carpenter says.

Navigating and policing such a nebulous space, even with California’s new laws, might not be simple. “The enforceability is really, really vague,” he says. Three days for a platform to remove deepfake election content is way too long by Carpenter’s measure in the current information ecosystem. "At the same time, it’s still very, very difficult for a platform to execute on. If you were going to make it shorter than that, it doesn’t cope with the reality that we’re in, which is that … false information on the internet travels at least 15 times faster than true information."

By the time corrections to deepfakes are disseminated, Carpenter says individuals may have already set their beliefs or taken action based on that false content.

Companies, especially platforms for publishing and sharing content, are under closer scrutiny with California’s new policy action, but Carpenter believes those companies already make some efforts to stem the tide of digital lies. “If you’re talking about the social media platforms, many of them want to do the right thing,” he says. “Facebook has a huge trust and safety department working, and they’re trying to build algorithms to stay on top of things, so they deserve at least a nod of credit.”

The story at X (formerly known as Twitter) is a bit different.

“Prior to Elon Musk taking over, there was a huge trust and safety contingent that worked at Twitter,” Carpenter says, “and then he riffed all of them. So, Twitter doesn’t necessarily get the nod of respect in trying to do the right things, but you do see them de-platform people every now and then if they’re doing super, super egregious stuff, but they’ve decided internally that their threshold for that is much higher than I think where a majority of the population would like it to be.”

While users of X may be aware of what they are getting into by continuing to use that platform, the potential disparity between platforms could bring turmoil. For example, Carpenter notes that content allowed to be created on X might be reshared on other platforms with users who are not as prepared to see and discern such content. Even if such deepfakes are eventually removed, the impact might already be felt. “They’ve got 72 hours to respond to that before they have to take it down, but how many minds have I influenced by that time?” Carpenter asks.

About the Author

You May Also Like