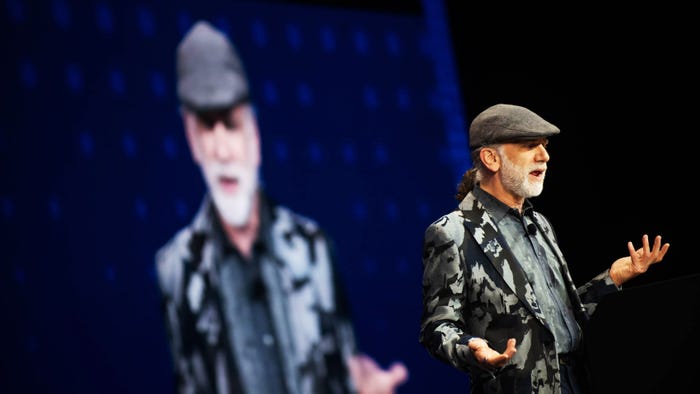

The Observer: The Vision Thing

Vision, like speed, is uncoachable, <B>Lou Bertin</B> says. You've either got it or you don't. In this business climate it, pays to have imagination and to use it wisely.

In sports, it's axiomatic that speed cannot be coached. Technique can be coached. Quickness, based on anticipation of how a play will unfold, most certainly can be coached. But speed? Utterly uncoachable. From much personal experience with many coaches over the years, I can attest that speed afoot, despite one's best efforts and eagerness to learn, cannot be coached. No way, no how. One is, it seems, fleet or one is not.

Similarly, it appears, people are gifted with vision or they're not. The vision I specifically write of here is not ocular but, rather, the sort of vision that lets individuals see a series of building blocks (think technologies) and envision how those building blocks can be used to construct imaginative, efficient, productive structures. That sort of vision is as uncoachable as speed, I have come to be believe.

That conclusion is born of a number of recent conversations with veteran executives on the business side and the technology side of their companies. It's a pity that such vision can't be coached, because it's increasingly apparent that vision is the single most determinative attribute (with the ability to educate a close second) to an IT executive's career success or lack thereof.

To a degree that's surprising and, occasionally, somewhat depressing. I've lately encountered a number of IT executives who are stuck in an odd sort of time warp where pressure (either internal or external) to innovate is an imperative to somehow be dodged, where the opportunity to apply technology in new ways to quickly gain competitive ground is a burden to be shunned, where technological change is simply a source of pain and not an endless source of nourishment for needy organizations.

Is change simple? More often than not, change is a complex, three-dimensional process. Is change painless? Never. Is change welcome? There's the million-dollar question. Change might not be welcome, but it surely needs to be encouraged at best and tolerated at worst at this time, in this economy, and in this competitive environment

Typical of the comments I've been hearing lately is one that came from a CEO: "Who's holding a gun to all of our heads anyway? Why do we need to look at every new thing that comes down the line? Why can't something last longer than six months before we think we need to buy a new one to keep up?" The answers to each of those questions betrays just how effective that executive's blinders are and how they typify a management and organizational style that's best dropped as quickly as one would a smallpox sample, were such a thing ever to find its way into our hands.

For one, the people holding a gun to the head of a company are, foremost, its competitors--either competitors that are familiar or those that can arise in the blink of an eye as a result of the emergence of the very technologies the executive in question laments. Enough said.

Why does the business need to look at every new thing that comes down the line? Because even if said business isn't looking, it can be assumed with absolute certainty that someone else is looking, not to mention the fact that looking--and learning--has never been easier, thanks to the ubiquity of the online medium.

Last comes the issue of why something can't last longer than six months before technological obsolescence sets in. The issue there isn't one of technical obsolescence, it's one of functional life span, and functional life spans are amazingly long-lived, as we're constantly being reminded. How many times has the mainframe died? How many iterations of thin-client devices do we need to experience, dating back to the green-screen terminal? Is there a statute of limitations on how long architectures that rely on massive data repositories can be allowed to exist?

Simply put, the issue of coping with and capitalizing on change isn't a question of what tools a company has at its disposal, but it unmistakably is an issue of how that company decides to use those tools, modest or extravagant, that are at its disposal. That thinking is hardly original, but the degree to which it's ignored or is simply incomprehensible is baffling, at least to me.

This brings us back to that troublesome and eternal "vision thing," where I think Mr. Einstein got it right when he said that "imagination is more important than knowledge," and Mr. Disney got it equally right when he referred to his employees as "imagineers."

Here's to the dreamers and the visionaries. Without them, and those smart enough to listen to them, we'd all be on the streets more quickly than we could possibly envision.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

How to Amplify DevOps with DevSecOps

May 22, 2024Generative AI: Use Cases and Risks in 2024

May 29, 2024Smart Service Management

June 4, 2024