The Observer: Cluttering Up The Network

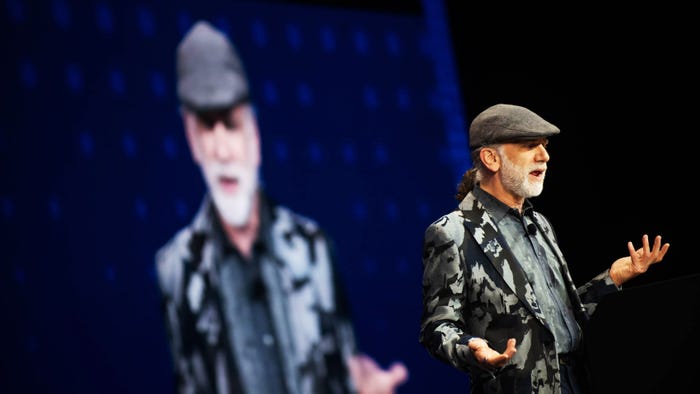

Nearly 70% of survey respondents say they're great collaborators. <B>Lou Bertin</B> thinks they're full of hot air. Here's why.

There are mornings when I wake up and the visage I see staring back at me in the mirror isn't my own miserable phiz, but that of Cary Grant. Such are the powers of self-delusion.

And self-delusion, it appears, is rampant among us, especially among those who responded to a recent InformationWeek poll on collaboration, where 69% of those contacted said they freely share information among colleagues and are, in fact, utterly marvelous collaborators. They may imagine themselves as superb at the art of collaboration, but the problem is that few (if, indeed, any) of us have ever met colleagues so willing to freely share information.

When I shared that particular datum with panelists and attendees during a recent series of InformationWeek forums, the consensus was one of bemusement at the twisting of reality that the finding indicates. In sum, everybody chuckled, but nobody took the findings as gospel.

I take the poll's findings as a source of both promise and peril. The promise is because the benefits of a collaborative workplace, a collaborative imperative among business partners, and (gasp!) even collaboration among competitors are becoming manifest. Peril: an increasingly collaborative commercial environment means that IT organizations are challenged to a ridiculous degree. Any weaknesses therein will be mercilessly exposed and exploited.

Even intramural collaboration is as much myth as reality, despite widespread and highly visible assertions to the contrary. At least, that's what my highly unscientific gut (fed by the opinions of hundreds of you) tells me. Sure, information is passed among various departments within even the smallest of enterprises, but is forwarding data or responding to requests truly "collaboration"? As a collaboration example, I think mere data interchange fails miserably.

Equally worthy of a failing grade on the collaboration test is sharing information only because companies have the equivalent of a Ruger pressed to their temples by an astonishingly big or astonishingly powerful business partner. The classic account of this circumstance usually begins, "When (pick one: Wal-Mart, GE, General Motors ... ) tells us to do X, we don't have any choice but to go along." That sort of thinking hardly betrays a commitment to an environment in which collaboration is a strategic tool.

And if companies indeed suddenly and mysteriously become enlightened and find themselves frenzied to share anything and everything, what would that actually accomplish? Absent a structure for doing so (not to mention an actual reason for all that sharing), the information being dealt around achieves nothing--other than to clutter up the network.

I'll spare all of you my utterly uninformed psychological analysis of why the "right" thing (in this case, strategic collaboration to specific ends) is so seldom the norm. However, the IT street (a close cousin of the mythical "Muslim street" so often cited these days) tells me that, when the vast majority of folks tell me they really do collaborate, it ain't necessarily so.

Moreover, were true collaboration to become the norm rather than the pitiable exception it remains, my surmise is that it would achieve little other than to point out how ill-equipped so many companies are to take advantage of collaboration's benefits. This capabilities shortfall isn't born of technological inadequacy or lack of available tools; it comes from human inadequacy.

Simply put, companies--and the people who populate them--aren't accustomed to the notion of freely sharing business intelligence for gain among all parties involved. The best of data, shared with the best of intent, still yields nothing--unless organizations are willing to sift, analyze, and assign weight to the information. This requires a concise answer to these questions: "Why do we do business?" "How do we do business?" and "With whom do we do business?" Try those out on your colleagues and see what consensus is reached--if any.

At the end of the day, the embrace of collaboration as an overarching corporate strategy--and nothing less than a total embrace of same will suffice--becomes a human issue, not a technological one. No argument can be made against the collaborative process (at least none that I've ever heard), yet so few companies are true collaborators. Unless and until the "vision thing" is remedied and incentives get individuals to change their stripes, we'll be able to revisit the collaboration issue for years on end before the needle moves appreciably.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

How to Amplify DevOps with DevSecOps

May 22, 2024Generative AI: Use Cases and Risks in 2024

May 29, 2024Smart Service Management

June 4, 2024