Wolfe's Den: Processors Rev Into Multicore Overdrive

With clock speeds at 3 GHz-plus and processors containing four or more cores, compute cycles are ubiquitous--we don't even think about them.

Download the entire June 14, 2010 issue,

Download the entire June 14, 2010 issue,

distributed in an all-digital format (registration required).

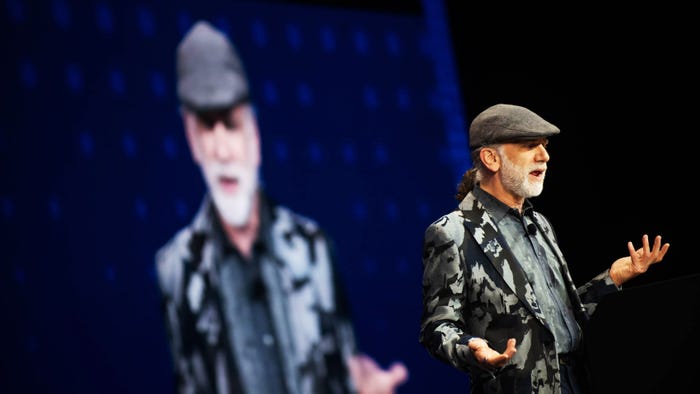

Alexander Wolfe

While server processing power is essentially free, it's still critically important. So Intel and AMD are taking their respective Xeon and Opteron processor lines to higher multicore counts and, in turn, delivering more raw computing horsepower than ever.

First, let me explain my thesis with a little history. As chips began the climb from the 12-MHz clock speed of the 1985-era 80386, the processor itself was the gating factor in system performance. It wasn't until the Pentium Pro in 1995, at 150 MHz, that the x86 architecture began to be robust enough to power servers.

Today, with clock speeds at 3 GHz-plus and processors containing four or more cores, compute cycles are ubiquitous; we don't even think about them. The gating factors in improving server performance now revolve around I/O (interprocessor, processor-to-memory, and storage access) and networking speeds.

Indeed, Xeon and Opteron are so successful that they've consigned RISC processors to very-high-end uses, such as complex transaction processing and stock market applications. Indeed, only three RISC architectures--Oracle/Sun UltraSparc, IBM Power, and Intel Itanium--survive.

We forget how fast and far we've come in the past decade. In 2003, AMD shook up the server market with Opteron, the first of a new category of 32/64-bit processors, powered by 64-bit instruction-set extensions. That development rapidly segued into a dual-core battle between Intel and AMD. Quad-core processors followed in late 2006.

In March 2009, with its launch of Nehalem (officially, the Xeon 5500), Intel gave a nod to the rise of I/O as the gating performance factor by finally jettisoning its front-side bus and adding an on-chip memory controller--something AMD did in the original Opteron in 2003. AMD, meantime, refreshed Opteron with Shanghai in late 2008 and added two more CPUs to create its six-core Istanbul in 2009.

All this one-upmanship suggests a tautological riddle: If there's ample processing power all around, why do Intel and AMD continue to push ahead? You wouldn't be philosophically wrong if you answered: Because they can.

The move toward more cores is also driven by the need to rein in energy consumption while providing enough processing heft to support heavy use of virtualization. Chip designers have been amazingly successful on the energy-efficiency front, reflected in an abundance of on-chip features that throttle cores and threads on and off. And while there's no hard correlation between physical multicore resources and virtualization--because virtualized instances make use of logical partitions on all available physical cores--it's pretty clear the one facilitates the other.

To get back to the 2010 server processor battle, both Intel and AMD are kicking things up a notch. Earlier this year, Intel released Nehalem EX, which includes quad-, six- and eight-core processors. Along with performance improvements, the eight-core Xeon in a two-socket (2P) configuration provides an obvious server consolidation play.

AMD's latest is the Magny-Cours (Opteron 6000). This next-gen architecture maxes out at 12 cores, with four memory channels. It's aimed at heavy workloads--business applications, databases, virtualization--says John Fruehe, AMD's director of server/workstation marketing. In the pipeline for 2011 is a 16-core Opteron, code-named Bulldozer, that will improve performance by 50% to 60%, he says.

It bears watching whether x86 performance advances will thrust the architecture deeper into RISC territory. "We're not going to hold Xeon back in any way," says Shannon Poulin, director of Intel's Xeon platform, hinting Xeon will begin folding in performance-related features that heretofore have been in Itanium only.

Editor's Note: This story was updated to correct the clock speed of the Pentium Pro.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

How to Amplify DevOps with DevSecOps

May 22, 2024Generative AI: Use Cases and Risks in 2024

May 29, 2024Smart Service Management

June 4, 2024