Why can't a simple formula replace the politically charged gerrymandering that's skewing our election processes?

When drawing new districts for Congress and the State Legislature, Florida has what sounds like a simple rule: "Districts shall be as nearly equal in population as is practicable; districts shall be compact; and districts shall, where feasible, utilize existing political and geographical boundaries."

Yet as I write this, the Legislature is meeting in special session to address a judge's ruling that lawmakers "made a mockery" of the redistricting procedure when they drew new maps in 2012, tilting them in favor of the Republican majority. Under the ruling, legislators must now redraw at least two districts -- potentially forcing elections in the affected areas to be postponed until after November.

In 2010, I campaigned for the FairDistricts amendment to the Florida constitution, which included the anti-gerrymandering rule quoted above, stating that districts should be compact. There was more to the legal language, of course, including clauses designed to avoid conflicts with other state and federal laws. But I thought the principles were pretty clear. While gathering petition signatures outside the library to get the measure on the ballot, I kept a map of some of the odder jigsaw puzzle piece districts in Florida taped to the reverse side of my clipboard. "What it will mean, if this passes," I would tell people, "is that districts will be neat little squares, pretty much, instead of crazy squiggles."

[Government innovation doesn't have to be an oxymoron, as long as it's based on open source principles. Read Federal IT Innovation Depends On Being Open.]

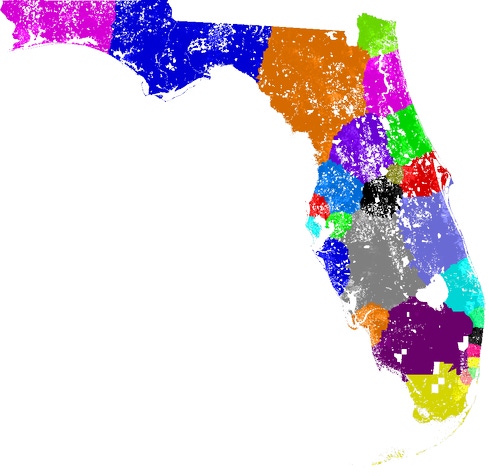

And yet somehow the redistricting process, following passage of the amendment, still produced this:

That is Congressional District 5, which stretches from Jacksonville to Orlando, a length from tip to tail of well over 100 miles.

How did this happen? Miami Herald columnist Fred Grimm explains it pretty well: Florida lawmakers can't be trusted to put public interests over their job security. By manipulating the map, lawmakers can choose their voters rather than letting the voters choose them. Republicans can design "safe districts" for Republicans, even if as a byproduct they also create some safe Democratic districts (from the cards thrown into the discard pile).

As Grimm notes, Democratic lawyers and their consultants have been guilty of the same sin in other states, including Florida when Democrats were in the majority. California was another example until a voter initiative moved the responsibility for redistricting to an independent commission not controlled by the Legislature. Grimm suggests Florida may need to do the same.

But why do we need a commission to implement what ought to be a simple formula? Here's the algorithm: Optimize for compact districts with an equal number of voters, matching the lines with city, county, and natural boundaries (such as rivers) where possible. Let software draw the map, with a minimum of human intervention. Yes, we'd still need humans in the loop for a sanity check (think of those times your GPS navigation system has sent you down a route that makes sense only to a computer).

Using software for redistricting would not be new -- one reason gerrymandering has gotten so rampant in recent years is that political consultants have applied geographic information systems and statistical analysis to the problem of optimizing districts for political advantage. But there is no reason the same technology couldn't be applied to optimizing for fair and even representation.

I'm not the first person to think of this. Via a Washington Post Wonkblog column, I learned of the open source compact district optimization software that Brian Olson created in his spare time. A Florida Congressional map created from 2010 census data would look like this:

Hypothetical compact Florida Congressional districts (source: bdistricting.com)

Neat little boxes -- that's what all lovers of Democracy should want, right?

Maybe not. District 5 was drawn to be a "minority majority" district, effectively a safe district for Rep. Corrine Brown, who is black, because of its concentration of black and minority voters. However, Leon County Circuit Judge Terry Lewis ruled that the way the legislature separated white from black -- in the process separating Republican-leaning and Democratic-leaning populations -- was unfair and biased. As Politico reports, Democratic support for the lawsuit challenging the districts has drawn the ire of the Congressional Black Caucus, which sees it as a threat to Rep. Brown's smooth reelection.

While Florida's redistricting ballot initiative was supposed to be non-partisan, it was backed more enthusiastically by Democrats, who have been the minority party in the Legislature for decades now (gerrymandering was more fun for them when they were in the majority). To preserve the support of black Democrats -- or at least prevent them from actively opposing the FairDistricts initiative -- the authors of the amendment slipped in this language: "Districts shall not be drawn with the intent or result of denying or abridging the equal opportunity of racial or language minorities to participate in the political process or to diminish their ability to elect representatives of their choice."

That provides some wiggle room for district lines that preserve concentrations of minority groups, even if they aren't neat little boxes. But I believe that using it to justify the shape of District 5 is too much of a stretch, and the judge thought so, too.

In explaining the thinking behind his algorithm to optimize for compactness, Brian Olson addresses some of the justifications for applying human judgment to the drawing of districts and why he finds them unconvincing.

Some might consider drawing the lines for minority majority representation or to preserve communities of interest to be "good gerrymandering," but somehow instances of "bad gerrymandering" always seems to outnumber good. "Until we clean up our representative democracy to give us better representation I think we should take away the map pen and make redistricting fully automatic and impartial," he writes.

What do you think? Which would you trust more -- an open source algorithm or your state representatives?

Mixing public and private can deliver the best of both cloud worlds. But beware management complexity, cost volatility, data protection, and other potential snafus. Get the new Hybrid Cloud Gotchas Tech Digest today. (Free registration required.)

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like