Our flash poll finds users feel more vulnerable about cloud security in general. No wonder: Apple's opening statement of indignation now sounds a little hollow.

The release of movie stars’ personal photos, raided from Apple’s iCloud, seemed to me like a calculated assault. Someone conceived of the most attention-getting way to embarrass iCloud operations on the eve of the release of the iPhone 6. And Apple appeared all too vulnerable to such an incident.

"A trove of naked photos and video content stolen from the stars appeared on the 4Chan chatroom site over the weekend. Questions about how the hackers got hold of the celebs' accounts began to center around a possible flaw in Apple's iCloud and Find My iPhone," reported my colleague Kelly Jackson Higgins for Dark Reading on Sept. 2. There were reports Apple had recently fixed a hole that would allow a brute-force password attack, she noted.

What better way to cast doubt on the security of iCloud than to scatter celebrities' personal information across the Internet? And just in case anyone missed it, make sure the words "Jennifer Lawrence" and "nude" or "naked" are combined in as many headlines as possible. If that was the attackers' goal, then it can't be denied, they in some measure succeeded.

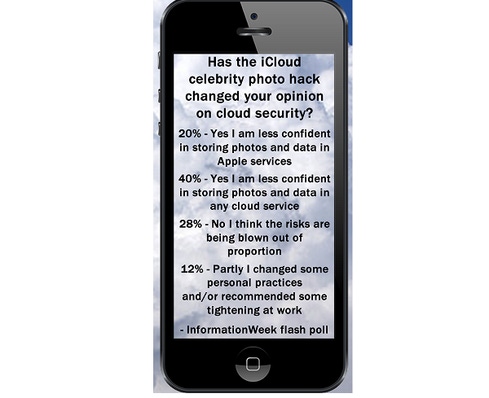

How successful were the scare tactics? We ran a flash poll to ask InformationWeek readers how the incident affected their view of cloud security. Twenty percent said they are now less confident storing photos and data in an Apple cloud service, and 40% said they are less confident doing so with any cloud service.

So how hard was it to obtain those photos? "None of the cases we have investigated has resulted from any breach in any of Apple's systems including iCloud or Find my iPhone," an Apple statement said soon after the incident. Meanwhile, it added, "We are continuing to work with law enforcement to help identify the criminals involved." The latter sentence has a certain satisfying ring to it. The proper authorities are on the case, and its outcome is all but a foregone conclusion.

But we shouldn't be too convinced of that. First of all, Apple left itself some weasel room in its statement. Forty hours after a headline-making breach, the best it could say was "none of the cases we have investigated has resulted in any breach." This also says that, at that late date, Apple hadn't investigated all the cases. If it had, it's possible one of the cases might incontrovertibly establish there had been a breach. The hole in the statement leaves enough wiggle room to drive a truckload of stolen backup tapes through.

And what if the offending party is a script kiddie who somehow took advantage of weaknesses in the Apple systems? When this has happened elsewhere, the authorities got only lightly involved and usually advised the offended party to tighten up its procedures. To which prison does Apple intend to sentence this criminal, just so his parents will know where to go to visit?

[It's time to dismantle the moat. See Mobile, Cloud, Partners: Where's The Weak Link?]

If the iCloud password system could be hit with a brute-force attack, then a modest amount of compute power could repeatedly try likely passwords based on knowledge gleaned from the target's frequent activity reports and personal doings. The names of children, pets, favorite activities, or locations could be tried in various spellings and combinations until one is found that works. The protection against brute-force attacks is to limit the number of password tries. But such a limit would interfere with those Apple customers who might have momentarily forgotten their passwords. Likewise, setting a requirement that a password be non-obvious -- containing capital letters, numbers, punctuation marks -- would have been another defense.

But as we all know, good security defenses slow the consumer impulse to get to a site and spend money. Vendors that are proud of their seamless vertical integration and ease of use are probably less likely to put barriers in the way of the typical user. On the contrary, it appears iCloud's security requirements were kept as simple as possible.

"Certain celebrity accounts were compromised by a very targeted attack on user names, passwords, and security questions," a regrettable incident, but "a practice that has become all too common on the Internet," Apple's statement continued. In short, it was individuals who were compromised, not Apple's systems. And to carry the logic a step further, it is the individuals who allowed their user names, passwords, and security questions to be guessed that are at fault. If Apple makes things easy for consumers to use, it's still not Apple's fault that some customers are less than stringent in following good practices as they use them.

This makes Apple's opening statement of indignation sound a little hollow. "When we learned of the theft, we were outraged and immediately mobilized Apple's engineers to discover the source. Our customers' privacy and security are of utmost importance to us." Yes, but it wasn't too hard to guess Jennifer Lawrence's password and steal her pictures, given the protections you provided.

Should this incident decrease consumer confidence in the security of cloud use? It should alert them that vendors of cloud services are interested in moving them to the goods; protecting their security is typically coming in a distant second, no matter what they say after a breach. If it's easy to remember your password on a cloud login system, it may also be easy to guess it by those who know a little something about you. And if you think lots of engineers and millions of users mean you must be using a secure system, try finding out what good security practices are and note the many ways you can improve on the minimal requirements your cloud vendor has laid in front of you.

Today's endpoint strategies need to center on protecting the user, not the device. Here's how to put people first. Get the new User-Focused Security issue of Dark Reading Tech Digest today. (Free registration required.)

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like