The War On Military Records

The era of big data has arrived on the battlefield and we need to find new ways to deal with it.

This same paradigm shift has also caused the vast expansion of records and material to preserve. Just 10 years ago, we were dealing with gigabytes of data. Now we are trying to manage terabytes and petabytes. In essence, the era of big data had arrived on the battlefield and we needed to find new ways to deal with it.

The volume of records that were successfully preserved by US Central Command in the second Gulf War amounted to more than 54 terabytes. That's more than 40 million files and documents! However, only a percentage of these records -- between 10 and 15 terabytes are actually deemed to be of a permanent nature by the National Archives.

That introduces another question: How does one separate the wheat from the chaff of a collection of records that if converted to paper would reach 270,000 feet high? And do that with only a staff of three?

The answer can be found using technology available from firms such as Active Navigation Inc. I first saw the potential of Active Navigation's File Analysis capabilities at the ARMA 2010 trade show and was impressed by the way File Analysis could extract value from content for which we had no previous knowledge, a form of blind discovery.

The tool allowed us to quickly get grasp an overall view of our information estate, quickly identify redundant, obsolete and trivial content (also known as ROT), and remove duplicate records. Reducing the total estate is crucial, and the way forward, because the alternative of keeping it all is simply no longer a viable option, given government IT budgets and the increasing costs of long term storage and back-up infrastructure.

For years, we in the records business have heard of such tools being called a game changer. To be honest, I was not a believer. I have since changed my mind. I'm now convinced, if appropriately combined with other records tools, these products can help government agencies, businesses, universities, and private companies save millions of dollars in un-needed storage, back-up infrastructure and eDiscovery costs.

These tools are valuable in other ways. Active Navigation, for instance, has the ability to identify privacy data (such as Social Security numbers) and ultimately augment the content with relevant metadata, extracted from the document itself, using natural language processing, making document identification more accurate and complete prior to handover to the National Archives and Records Administration.

The modern "War on Records" has just begun. Big data has presented a monumental challenge for today's Records and Information Managers. To combat this problem, new innovative systems are often required. When I was presented with the challenges of the OIF collection I did not look for twentieth century solutions for a twenty-first century problem. I truly believe that if technology is the problem, better technology is often the solution to it.

Today's records and information management technology has improved to such a point that even organizations with minimal staffing can deal with the big data problems persistent in both the private and public business spheres. Our nation's historical record depends on it!

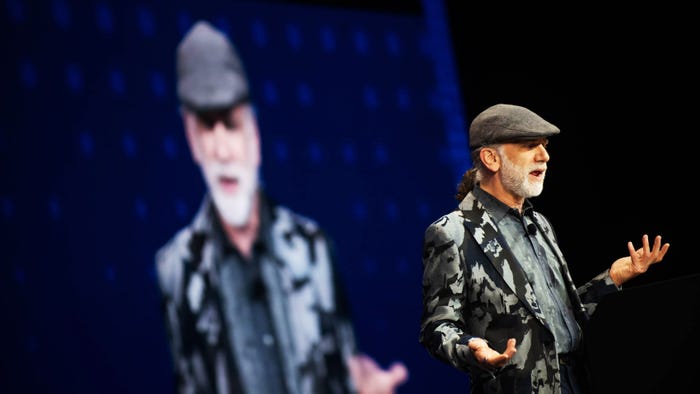

Joel Westphal is the Agency Records Officer for the Office of Personnel Management in Washington, D.C. He also serves on the National Archives Federal Records Council. He previously worked at US Central Command, as the Chief, Records Management Section.

IT groups need data analytics software that's visual and accessible. Vendors are getting the message. Also in the State Of Analytics issue of InformationWeek: SAP CEO envisions a younger, greener, cloudier company. (Free registration required.)

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

How to Amplify DevOps with DevSecOps

May 22, 2024Generative AI: Use Cases and Risks in 2024

May 29, 2024Smart Service Management

June 4, 2024