Healthcare Devices: Security Researchers Sound Alarms

Default usernames, weak passwords, and widespread Windows XP Embedded systems are cause for concern, SANS Institute researchers say.

Hackers Outsmart Pacemakers, Fitbits: Worried Yet?

Hackers Outsmart Pacemakers, Fitbits: Worried Yet? (Click image for larger view and slideshow.)

Who wants to be hooked up to a kidney dialysis machine that's been compromised by fraudsters?

That's one alarming prospect facing hospital goers, according to a "Healthcare Cyberthreat Report" published this week by the SANS Institute (registration required). The study is based on data collected from September 2012 to October 2013 by the security vendor Norse via millions of endpoint sensors and honeypots located in enterprise networks, large-scale datacenters, and major Internet exchanges. It reveals widespread health-network configuration and patching problems, as well as other fundamental errors involving information security.

As a result, during that 13-month period, researchers found evidence that 375 different healthcare networks had been compromised by attackers. "We were shocked at [the number of] devices that were wide open to the Internet that would provide adversaries with considerable power and access not only for a breach, but -- for those who are skilled -- even to conduct malicious acts," Sam Glines, CEO of Norse, told us by phone.

[Ready for the convergence of patient data, social platforms, and analytics? See HIMSS14 Preview: Enabling Today's Digital Doctor.]

Overall, the report found that the most frequently compromised types of health organizations were healthcare providers (in 72% of cases), followed by healthcare business partners (10%), health plans (6%), and pharmaceutical concerns (3%). Meanwhile, the list of compromised healthcare services and devices included VPN servers, surveillance cameras, radiology equipment, videoconferencing equipment, and home healthcare monitoring devices. "When we started seeing dialysis machines being used to conduct fraudulent credit card transactions a few months ago, we knew things were pretty bad," Glines said.

Device configuration errors undercut network security

When it comes to attackers being able to compromise healthcare networks, poorly configured devices are largely to blame, including not only VPN systems, but also VoIP servers. One example cited by Norse was an Internet-accessible VoIP system with an HTTP login page, which would be susceptible to brute-force attacks, or having a user's credentials sniffed if the site were accessed using public WiFi.

Many healthcare networks also appear to be using devices for which the default -- and publicly known -- admin usernames haven't been changed. In other cases, security administrators have failed to give each device a unique password.

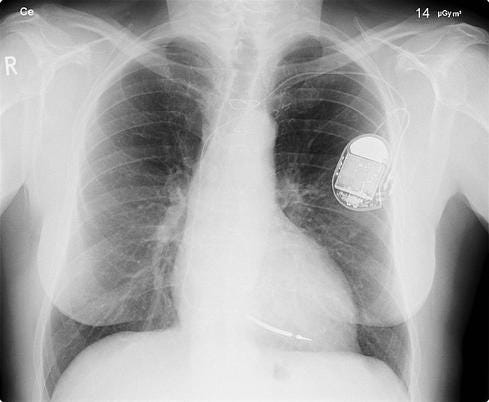

Figure 1:  (Source: Wikipedia)

(Source: Wikipedia)

For example, researchers found a "network infrastructure profile" document for a healthcare organization on 4shared.com -- a Pastebin-like site -- that "includes IP addresses of core networking infrastructure, firewalls, and even the patient health records system inside the organization," according to a research document shared by Norse. The document also reveals that both the organization's SonicWall firewall and SigmaSafe electronic health records (EHR) system -- among other systems -- are set to use their default admin usernames. In addition, they all share the same password, which ends with a six-number sequence that begins with the number one and ends with the number six.

Warning: Small office device vulnerabilities abound

But not every device vulnerability traces to poor password hygiene, according to research recently conducted by the security firm Tripwire. "We were looking through consumer routers -- primarily products that are marketed for home users, but which also make their way into real estate offices, small medical practices, car dealerships -- which are made with features in mind, but not really security in mind," Craig Young, a Tripwire security researcher, told us by phone.

In particular, Tripwire reviewed the 50 top-selling routers available on Amazon and found that at least 74% of them are vulnerable to some type of attack. Though Tripwire didn't get its hands on all those routers, 34% of them were vulnerable to attacks that had been published to exploit sites such as Exploit Database and Packet Storm. But another 40% sported vulnerabilities that Tripwire's researchers, with a bit of hands-on testing, were able to discover after investing only a modicum of time and energy.

Tripwire has notified the relevant vendors, but patches have yet to be issued for all the vulnerable devices. Furthermore, when patches are released, few device owners learn about them unless they happen to access their device's configuration screen and update the firmware. According to a recent survey conducted by Tripwire, 68% of consumers said they didn't know how to update the firmware on their wireless router.

Healthcare security is better than some industries

In the medical realm, of course, IT departments are meant to hold their business to a higher standard, and according to further research from Tripwire, the healthcare sector scores better than some industries -- though there's still substantial room for improvement.

For example, 76% of healthcare IT professionals surveyed by Tripwire reported that they'd changed the default IP address of their corporate wireless routers, versus an average of 59% of respondents overall. Only

one-quarter of healthcare respondents said all their routers still used default IP addresses, versus an overall average of 41%. But 37% of healthcare organizations -- versus 14% of organizations on average -- reported that all of their routers were using WiFi Protected Setup (WPS), which is a flawed networking standard that can be compromised to gain access to the device.

For organizations tasked with protecting people's personal medical data -- and which must comply with the Healthcare Insurance Portability and Accountability Act -- is there any excuse for more than one-third of them still using WPS?

Furthermore, 51% of IT professionals in the healthcare sector said their employees work remotely -- versus an overall average of 43% -- which means that securing remote-access technologies is especially important for the healthcare sector.

According to the Norse report, however, the most frequently compromised systems -- accounting for almost one-third of the malicious healthcare IP addresses detected during its study -- were healthcare organizations' remote-access VPN systems. According to Norse, those systems were most likely compromised because the organization wasn't enforcing a strong password policy. According to the SANS study, "without a strong password policy in place, even strong SSL VPN authentication can be easily compromised by brute-force password guessing or dictionary attacks."

Patching devices: Some hospitals lag

Beyond strong password policies, another recurring healthcare IT problem is poor patch hygiene, especially for devices that run firmware based on older or outdated operating systems. "A lot of equipment that you find in hospitals is actually hardware that's running Windows XP Embedded, and it's not getting patched on a regular basis," said Tripwire's Young.

Part of the problem is that, after Microsoft issues an update or security fix, vendors must build a new version of their firmware and then test every system that uses the firmware -- to ensure that X-ray machines, for example, still behave as they should -- before distributing it to customers. Until that happens, healthcare organizations remain exposed to attackers targeting known vulnerabilities.

Even when those patches arrive, applying them takes further time. For example, whereas a retailer with 100 or 1,000 identical point-of-sale systems might be able to push firmware updates from a central server -- such as Microsoft's System Center Configuration Manager -- most medical facilities sport a very heterogeneous medical device infrastructure. "On a lot of these devices... you need to get new software from the vendor, go to the device, turn it off and on, and use media that will replace all the software on the device," said Young. Doing so will likely wipe all presets and require the devices to be reconfigured. "An X-ray machine, an MRI machine, a dialysis pump: all sorts of things that are going to need individual configurations."

Windows XP Embedded life support ends

What happens when security fixes are no longer available for medical devices, yet those devices are vulnerable to known attacks? Microsoft will cease supporting not only Windows XP on April 7, but also Windows XP Professional for Embedded Systems, on which many medical devices run.

Microsoft said Feb. 17 that four other versions of Windows XP Embedded will continue to be supported -- meaning they'll still get patched -- since they've been released more recently. For example, Windows XP Embedded SP3 will be supported until 2016. Windows Embedded POSReady 2009 -- for POS systems -- will be supported until 2019.

However, just because Microsoft stops issuing patches doesn't mean devices that run the unsupported operating system will be scrapped. This month, for example, researchers at Qualys obtained a second-hand version of a type of X-ray scanner used by Transportation Security Administration screeners in airports -- also used at embassies and court buildings -- and found that the machine was running Windows 98 and stored access credentials in plain text, which could allow an attacker to take over the systems, e.g., to project fake images. That example doesn't hail from the healthcare field, but it does show that devices don't die just because an operating system vendor announces that the software has reached its "end of life."

Vulnerable devices: Attackers' stepping stones

Besides exploiting vulnerable network-connected devices, attackers can use them to launch exploits against other sites. "All of these compromised devices, not only are they available to be used for a breach of data, but they're also used as attack points against other adversaries," Norse's Glines said. They "just give attackers more options for launching attacks."

Over the past couple of weeks, Johannes Ullrich, CTO of the SANS Internet Storm Center, has detailed the discovery of a worm, named "TheMoon," that uses a series of exploits to compromise some types of small-office routers, including the Linksys E product line.

According to a blog post from the security researcher Bernardo Rodriques, the worm was used to build a "stealth router-based botnet" -- thought to comprise at least 1,000 exploited devices -- that's been launching distributed denial-of-service attacks against dronebl, which is billed as being a "database of abusable and 'rooted' machines."

The worm wasn't built to target PCs -- meaning anything built on an x86 processor -- but rather to target MIPS-based Linux devices, including some types of the aforementioned Linksys routers. In addition, vulnerable devices must have telnet, SSH, or the web-based interfaces enabled via the WAN -- none of which Linksys ships enabled by default -- as well as have weak username and password combinations or else weak firmware daemons, said Rodriques.

This is hardly the first time that security researchers have sounded warnings about non-PC, network-connected devices that can be compromised

and used to launch attacks. Last year, for example, Craig Heffner, a vulnerability researcher at Tactical Network Solutions, discovered an authentication bypass flaw in D-Link routers that would allow an attacker to log into any such Internet-connected device -- no matter their security settings -- and install malicious firmware.

Thankfully, TheMoon didn't involve malicious firmware, which had the added benefit of making the malware easy to expunge from infected devices. Instead, the worm appeared to be relatively opportunistic and designed just to gain access to vulnerable devices and then run its attack script to DDoS the dronebl site.

Healthcare fix: Start with information security basics

TheMoon demonstrates how easily a determined attacker can tap an undocumented flaw on a network-connected device to use it for his own purposes. But what happens when the exploited flaws are of an IT department's own making -- for example, because it's failed to change factory-set usernames or passwords? "The point is that, if you're going to buy a firewall, you'd better change the frickin' default password," said Glines.

Of course, that assumes a firewall is even being used. According to Glines, "what we're also seeing within this industry is quite a few appliances -- surveillance cameras, printers, and so on -- that run full Linux stacks that have no security on them whatsoever," nor have they been placed behind firewalls.

From a security defense standpoint, setting unique passwords and using firewalls should be just the start. The SANS report recommends that every organization -- healthcare included -- implement its list of 20 critical security controls, which include assessing the IT infrastructure to know which types of devices are actually running on the network. That's especially important in hospital environments, which may be full of nontraditional IT systems, such as network-connected medical instruments and MRI scanners.

Other crucial SANS steps include thinking like an attacker -- how would you attempt to steal medical information? -- as well as network monitoring to watch for signs of network infiltration and post-breach data exfiltration.

Patient data feeds prescription fraud

As the compromise of 375 different networks -- reported in the SANS study -- highlights, healthcare intrusions aren't an academic issue. "This level of compromise and control could easily lead to a wide range of criminal activities," Barbara Filkins, the SANS analyst who wrote the "Healthcare Cyberthreat Report," said in a press release. "For example, hackers can engage in widespread theft of patient information that includes everything from medical conditions to social security numbers to home addresses, and they can even manipulate medical devices used to administer critical care."

The vast majority of online attacks trace to criminals seeking financial gain by using things like banking malware to steal businesses' or consumers' online banking credentials. Healthcare systems, however, also offer criminals a potential revenue source; they can seize information that can be used to perpetrate Medicare fraud or prescription fraud. "The value of a medical record that gets stolen is $50 to $60 per record today, whereas a credit card is about $20," said Glines at Norse.

With credit card fraud, consumers can change accounts, or they can use ID theft monitoring services to cut down on some of the hours of cleanup hassle they'll likely face. But people who have their medical records stolen have fewer options or types of consumer protection. "If you're the victim of medical record fraud, [cleanup] costs fall more directly on the consumer, not to mention the privacy of your information being on the Internet is more concerning," Glines said.

Is HIPAA keeping security healthy?

For healthcare organizations, of course, failing to properly secure patient data opens them up to HIPAA fines and enforcement actions. In 2013, according to Filkins at SANS, individual HIPAA fines started at $150,000 and peaked with the $1.7 million fine against WellPoint for failing to protect information on more than 600,000 patients, which was left easily accessible via the Internet.

Despite the threat of such fines, 18 years after HIPAA was passed, and with the White House itself struggling to make the HealthCare.gov insurance portal secure, the SANS study suggests that many organizations that touch patient data still aren't taking the health of their IT infrastructure seriously.

Download Healthcare IT In The Obamacare Era, the InformationWeek Healthcare digital issue on changes driven by regulation. Modern technology created the opportunity to restructure the healthcare industry around accountable care organizations, but ACOs also put new demands on IT.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

How to Amplify DevOps with DevSecOps

May 22, 2024Generative AI: Use Cases and Risks in 2024

May 29, 2024Smart Service Management

June 4, 2024