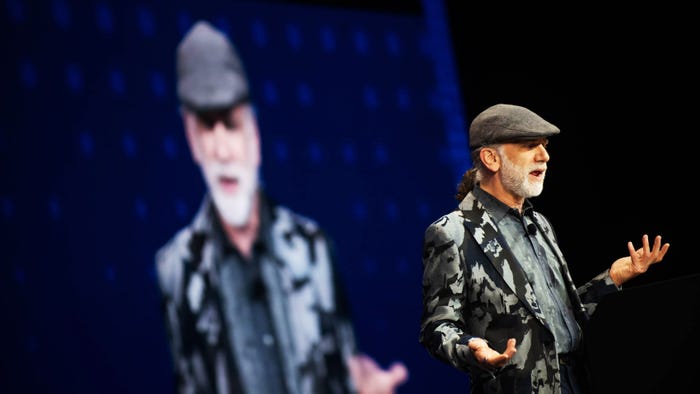

Former Uber CSO Sullivan on Engaging the Security Community

In the second part of his interview with InformationWeek, Joseph Sullivan talks about what CSOs can learn from his experience.

Joseph Sullivan was the CSO of Uber. In 2017, he was fired when new management initiated an investigation into a 2016 data breach at the company. Subsequently, Sullivan was charged with covering up the incident and sentenced to serve probation.

In the second part of his interview with InformationWeek, Sullivan delves into his perspective on the trial, the impact of his sentence, and how he plans to work with the security community and government going forward.

The interview has been edited for clarity. The first part of the interview can be found here.

How do you view the roles of Uber as a company, its legal team, and the other executives at the company in everything that has happened: the incident response, the trial, and its outcome?

That's a super broad question. I have a lot of different feelings and perspectives. One of the things that was really hard for me was that I had built in a very short time a really good team doing security at Uber. When I started, Uber had a tiny little information security team, a tiny little trust and safety team, a tiny little fraud team, a tiny little physical security team, a tiny little investigations team. And I took over all of those areas and built them out. I hired a CISO. I built out the InfoSec team, hired a head of risk, and built out the fraud teams. So, I built out a team of hundreds of people who are very dedicated, very hard-working, very committed to the mission. A lot of them had followed me from other companies. So, I think more than 40 people on my team had worked for me or with me at other companies before.

Uber was a tough place, culturally, in terms of how the world viewed it. We woke up every day to negative articles, but we had a really inspiring mission. We believed in the potential of Uber as a platform for making cities better and more livable and transportation better.

So, to be ripped out of there all of a sudden, when I got fired in the fall of 2017 -- I got fired and was subject to all of a sudden swirling lawyers and lawsuits and class actions and everybody's represented and I'm not allowed to talk to anybody on my team. If I were to start reaching out to them and even just to say, “How are you doing? Are you okay?” It would be viewed as tampering or something like that. And so, all the lawyers were like disconnect.

So, I had built this amazing team, and I was not allowed to speak with them. To tell them that I was sorry. And then they were stuck inside that company dealing with a situation where they were told that their boss was an evil villain. That was a really hard thing to go through because there were a lot of people that I was close with.

Now, the judge in your case expressed surprise that it was you who was standing trial. How do you feel about the personal accountability that you have in this case? Do you think you should have been held accountable alone?

When I think about the situation and I step back, I think that there's a few things. One is that the world that we live and practice security in right now is very different than the world of 2016. Things have evolved a lot in a bunch of different ways, partially I think as a result of this case. There's a lot more talk about role definition, accountability, transparency. So, a lot of good things have come out of it in terms of people understanding their risks.

It's a precarious world in which you learn about the risks through enforcement actions rather than through clear, upfront guidance and legislation. We haven't had clear national legislation explaining responsibilities around disclosures to the extent that would be ideal.

I feel like we're in a very different place now. Bug bounty programs are much more stabilized and used. We were kind of on the bleeding edge. I'd always been on the cutting edge of pushing out bug bounty programs. They're more ubiquitous now, but more conservative, I guess, in some ways.

So, a lot of things have changed. I still think there needs to be a lot more change. I don't think we want to have a world where it's all adversarial. I feel that my team did a really great job from an investigation standpoint. I don't think we see companies committing to doing that level of investigation.

Is a better outcome for a company to just throw up their arms and say we lost the data, let's go declare a data breach and move on? Or, to do the investigation, protect the customer's data, and figure out a way to do the disclosures? That's probably the ideal world where we want to encourage transparency. We want to encourage companies to do the right thing in terms of investigations, and we want to have a better collaborative relationship between companies and the government so that together these investigations are done even better in the future. And I'm not sure we’re there yet, and that's the thing that I want to speak up more about and figure out how we can do better.

What do you think of your sentence, the trial outcome? Do you think it is fair?

Well, my case still goes on. I am appealing some of the legal decisions that I think are important to have further debate about. So, we are going forward with an appeal.

I was very grateful that the judge gave me a sentence of probation. I was very scared for a very long time that I was going to be sentenced to time in prison. When you have that looming over you, it's very hard to live and make plans. You can't. And so, I have a family. I couldn't make plans for a summer vacation with them or even summer camps for them or things that I wanted to think about. Having a case like that hanging over you for as long as I did was a very paralyzing thing for a very long time.

Now, having a felony conviction is very impactful in terms of what I'm allowed to do in my career going forward. Opportunities are not there because of the conviction. It's interesting; I think the facts of the case could be a blocker to me getting an opportunity, but the real blocker is having a felony conviction because there's just a lot of jobs that you can't do in the security profession as a result.

You’ve been speaking with CISOs about your experience since 2017. How have they responded to what you have to say?

I think that every CISO appreciates the conversation. CISO is a lonely role. There's a really amazing camaraderie between security executives that I'm not sure exists in any other kind of leadership role. The CISO role is pretty new compared to the other leadership roles. It's far from settled what kind of background is ideal for the role. It's far from settled where the person in the role should report. It’s far from settled what kind of a budget you're going to get. It's far from settled in terms of what type of decision-making power you're going to have.

So, as a result, I think security leaders often feel lonely and on an island. They have an executive team above them that expects them to know all the answers about security, and then they have a team underneath them that expects them to know all the answers about security. So, they can't betray ignorance to anybody without undermining their role. And so, the security leader community often turns to each other for support, for guidance. There are a good number of Slack channels and conferences that are just CISOs talking through the role and asking for best practices and advice on how to deal with hard situations.

Since I got fired from Uber in 2017, I've been contacted by many, many CISOs when they felt like they were in the hot seat. I've also talked to many CISOs in group conversations, more thinking ahead. So, I’ve lived through a lot of different CISO experiences these last few years.

What do you think are the biggest lessons CISOs can take away from your experience going forward?

Well, one of the hard lessons is the idea that the world believes we have more power than we have. If you stop a random person on the street and you tell them a company had a security issue, who should be held accountable? They have a person called chief security officer. Who's going to be held accountable? That person. Every CISO would say, but, but, but, but I don't have unlimited authority. But I don't have unlimited resources. But I'm a voice for other people. I am representing our customers in our exec meetings and board meetings. But it doesn't mean, I get to build all I want, and I get to reduce all the risks I want.

I think that's the ultimate worry for a lot of CISOs. Why am I accountable for a security failure if I don't get unlimited resources and unlimited power? But that's not the reality of the real business world. Every leader inside every company fights for every drop of resources they get. And the CEO is balancing them all out in a path to running a successful business. And so, every day, the CEO and the board make decisions around, do we give another dollar to the product or marketing or sales teams, or do we give it to a team that reduces risk? So, you're always competing for resources, and you don't always feel that the company's following your advice.

You touched on this earlier. You plan to work with the CISO community to push for greater clarity around security incident and data breach laws and disclosure. What changes do you hope to see as a result of that effort?

When you look at the cybersecurity landscape and you think about investigations and how do we prevent the most harm by building really good security upfront and then make sure that security incidents are responded to well and consumers are protected. Because so much of the technical landscape is in the hands of the private sector, there has to be a better relationship between government and the private sector than we have right now. The government and the private sector need to be on the same team, not adversaries. My worry from my case, in particular, is that it’s kind of doubled down on the image of, or the perception of, an adversarial situation between government and the private sector.

We're not going to be able to stop the real attackers, the real people who are trying to harm our customers if we're in an adversarial relationship between the private sector and the government.

Right now, you are now CEO of the nonprofit Ukraine Friends. Tell me a little bit about your work there.

So, last year I was working at Cloudflare. So, I spent a bit over four years working for Cloudflare, which is a company that provides internet security. And one of the most rewarding things I got to work on there was when last winter in 2022 the US government asked us to help the government of Ukraine from a cybersecurity standpoint. So, I was very actively involved in that up until the time that I left Cloudflare last fall.

With the outcome of the trial, I just felt like I needed to get to work on something. I wanted to do something in the nonprofit space. So, I reached out to a bunch of people and said I would really like to do something supporting Ukraine, from a cybersecurity standpoint was my initial thought. I asked the same recruiter who had placed me at Uber and at Cloudflare to help find me a role as a volunteer at a nonprofit helping Ukraine.

He called me a month later and said I had my team of recruiters reach out to all the nonprofits. We actually found one that they're transitioning their old CEO, and they could use a CEO. Well, I was looking for a volunteer project. I wasn't expecting to be asked to be the CEO of a nonprofit, but I spent some time with the founders and board and felt like it was a really compelling mission and opportunity. So, I agreed in January and signed on to be their CEO.

What that means is I run a team that provides humanitarian aid to the people Ukraine. We're currently focused on two main areas. One is medical aid and equipment. We provide first aid kits, more than I think any other nonprofit, into Ukraine. We have a couple of warehouses in Ukraine and Poland. So, we bring medical equipment and put together first aid kits and distribute them. Those first aid kits are on every train in the country and used by first responders and to a certain extent by members of the military if they don't have their own equipment, first aid gear, and things like that. So, anybody who needs it, we're there to help them.

The second thing we do, this year a new initiative that I kicked off. We're focused on the mental health of kids and families that are stuck in the war zone. More than half the kids in Ukraine are in remote learning, and of those, probably half of those kids don't even have their own computer for doing remote learning. They're in remote learning because the schools have been blown up or they're afraid to go to school or they are displaced and far from home. We don't want them to be a lost generation of kids. We want them to be able to keep up their education. It's good for their mental health to be engaged, interacting with other kids, teachers, and everything.

So, we gather laptops from companies that are ready to recycle them. So, a two-year-old MacBook Pro from a Silicon Valley company shipped over to Ukraine is fundamentally life-changing for a kid there. So, that's a project that I've spent a lot of time and energy on. I brought a bunch of laptops over to Ukraine when I went a month and a half ago. Now, we really have that kind of flywheel going where I'm getting lots of laptops sent over there. Because it's a mental health effort too, we put this sticker on the laptops with a lot of resources, whether it's lifeline for a suicide prevention hotline, or the First Lady of Ukraine has done a bunch of stuff on mental health. So, we put her information on the laptops, and we have some anxiety-reducing breathing exercises and stuff like that we put on there.

What comes next? How do you view your career path going forward?

I'm planning on doing a couple of things that we talked about. So, number one, I'm going to continue on as the CEO of Ukraine Friends. I'm trying to do fundraising, trying to support kids in Ukraine. And I'm planning my next trip to Ukraine right now for June and continuing that work. It's very rewarding. As soon as I went to Ukraine, people figured out my background in cybersecurity. So, I've been able to help out from a cybersecurity standpoint here and there.

I think what's happening in Ukraine from a cybersecurity standpoint is -- I don't know what the right word is: cutting edge or fascinating or terrible all at once. Getting to see some of what's really happening in the world of cybercrime, cyber war up close. Continuing to learn and grow as a result and being able to participate in that and doing some training for organizations inside Ukraine on cyber resilience. So, that's one category: trying to work to support Ukraine’s people.

Then the second category, I do want to continue to engage with the security community and government on how we do better. I've already committed to speak at a couple of conferences.

My goal is to talk about the case and the lessons learned from it and make sure that they're really learned. Also, being outside of it all, not working at a company as a CISO and not working in the government as someone doing cybersecurity, it gives me the opportunity to have a more direct voice in constructive ways, hopefully. I'm not constrained by like, oh, I can't say something because of my employer. I can't say something because I work for the government. I think I can constructively stir the pot, hopefully.

How do you feel about the impact of the trial and its outcome on you personally and professionally?

There's a lot of impact. I wouldn't wish it on anyone, what I've had to go through. The impact that it’s had on my family. With three daughters having to live with it for almost the last seven years. I’ve had to watch them struggle with how to deal with it at school. Missing school because of the trial. Missing school because of other things related to it. Having to see my name trashed in the media over and over. My integrity questioned. My family has had to deal with that for a long time. People who stood by me have had to deal with that for a long time. That has been hard.

When you get charged with a crime, the banks stop working with you. The insurance companies stop working with you. I had no idea.

I had done work when I was at Uber on reentry programs and trying to make sure that people who had convictions could still drive for Uber if there was no real risk associated with them. We'd actually gotten some state laws changed. You hope that a person's worst day doesn't stay with them forever and prevent them from going forward in the world.

I've talked to some people. I do want to raise awareness of our criminal justice system and the impact it has on people. I'm very fortunate in that I had a really great support system around me of family and friends. I was in an economically better situation than most people who face the criminal justice system. It's a tough slog to get through that world with your head up. I feel very fortunate that I was able to come through it as well as I have.

I'm definitely frustrated. There is a lot I'm not allowed to do. It is not just voting and not being able to carry a gun. It's the economic opportunities or opening up a bank account or 401(k) at a lot of organizations. There's a lot of impact that cases have.

At the same time, I'm a much more intentional person because of having had the scrutiny of this case. I am much more focused on the right things because of what I've had to go through with this case. I think I'm a better parent. I think I'm a better friend. I think I’m a better family member. I think I care more about going and doing volunteer work and giving back because of everything I've experienced through the case.

Are there any other thoughts about the incident at Uber and everything that followed that you would like to share? I know we’ve talked about a lot.

I keep going back to what the judge said at the sentencing hearing. The judge said that this was an unprecedented case. I didn't act for financial gain. I didn't lie to a government officer. I didn't tell anybody else to lie. The government's case was to look at a bunch of different documents and snippets from conversations and weave together a theory of what was inside my head. We need to make sure that we don't get into situations where people in my role are subject to someone trying to read their mind afterwards because there's not going to be the benefit of the doubt.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

How to Amplify DevOps with DevSecOps

May 22, 2024Generative AI: Use Cases and Risks in 2024

May 29, 2024Smart Service Management

June 4, 2024