Many CIOs have their doubts. In this series, we examine why cloud costs remain so hard to judge.

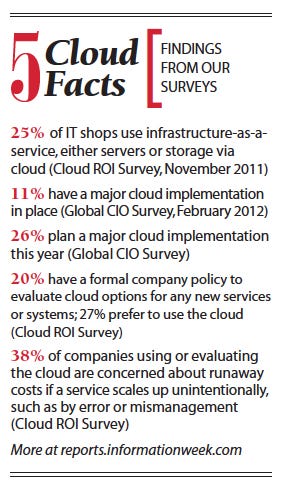

Public cloud infrastructure, the pay-as-you-use server and storage services sold by the likes of Amazon, Microsoft, and Rackspace, is getting some serious test-drives this year. About one-fourth of IT execs in our Global CIO Survey say they plan a major project this year to bring the public cloud into their IT infrastructure, compared with just 11% who have such services in place now.

But there's a cloud of doubt hanging over cloud infrastructure. IT execs, especially at big, established companies, are asking themselves: Are these services really less expensive than the capacity provisioned from my own data center?

Art Wittmann, InformationWeek's resident cloud curmudgeon, laid out a simple thesis in a column earlier this year: CPU performance and drive storage capacity keep climbing at logarithmic rates, but cloud infrastructure vendors aren't providing all of those implied cost savings back to their customers. "The Moore's Law advantage is immense and isn't something you should give up lightly, but some cloud providers are asking you to do exactly that," Wittmann wrote (see "Does The Cloud Keep Pace With Moore's Law?").

A big part of the problem is that the pricing structures are difficult to compare. Enterprise data centers have an annual budget that accounts for a mix of operational and capital expenses. Cloud services are usually based on a per-hour or other per-use charge. Even if IT organizations can approximate the hardware and software costs to run a given computing task on premises, they still need to figure in the job's share of the data center space and electricity bill. What share of network management, storage management, and system administration time should be allocated to one on-premises IT service? Usually, IT has only limited visibility into those factors on a service-by-service basis, so it becomes a guesstimate.

"It's a problem that has always existed," says Larry Godec, CIO at First American Financial, which had an acute case of hard-to-decipher costs, thanks to heterogeneous systems and duplicate applications that came with several acquisitions of title insurance and mortgage settlement companies. Shortly after becoming CIO in 2010, Godec implemented a cloud-based IT accounting system, Apptio, to get a better view into the cost of his systems. It required lots of data on existing applications, the hours of programmer time that went into building them, and the resources on which they run. There's a service modeling component to show all of the costs for internally provisioned services, and Godec thinks that feature will help it compare those to public cloud services, a process it has just started. But even a year into production, his staff continues adding information to the modeling system to get the assessment right. "It's an ongoing process," says Godec, who has since taken a seat on the Apptio board. "I wouldn't call it immature, but we still have a lot of work to do."

Even if IT organizations can get a handle on their in-house costs, comparing the pricing from the various infrastructure vendors can be confusing.

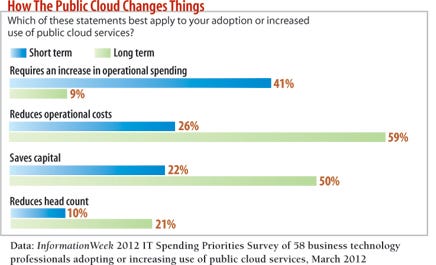

Despite this uncertainty, a good number of IT pros still seem confident in the cloud's cost saving potential in the long term. In the InformationWeek IT Spending Priorities Survey, we asked 58 IT pros who are using or adopting public cloud services about the economics. While 59% think cloud computing will raise costs short term, 74% say it'll lower costs long term. Fifty-nine percent think it'll lower operating costs long term, and half think it'll lower capital costs.

Those lower operating costs are what Jim Comfort, IBM's VP of cloud management, hangs his hat on. The real payoff is from a more efficient operating environment, from easier management and economies of scale in a standardized, x86-server cloud data center, he says. But since most companies can't say with much clarity what it costs them to deliver a particular IT service, measuring the payoff from moving to the cloud becomes a murky exercise.

Tough Comparisons

What's the answer to skeptics who think falling hardware prices aren't matched by falling cloud prices?

One answer: Public cloud infrastructure as a service, such as Amazon Web Services EC2 or CenturyLink Savvis, is a system and not just a hardware component, and the prices on systems have never dropped as steeply as components. The buyers of disks or CPUs that keep up with Moore's Law still have to install, operate, and update those systems themselves, while the cloud user can fire the people who were running the on-premises IT systems or free them up to take on new business development tasks.

However, rarely do we hear the cloud business case made around the cash savings from firing a lot of staff--just 21% of the respondents to our IT spending survey expect reduced head count long term.

Anecdotally, the business case is often made around agility--dealing better with spikes of activity or moving more quickly to meet a changing business need. That's the business case that worked for GSD&M, a 500-person Austin, Texas, advertising agency, when it pitched an online promotion last holiday season for Marshalls stores.

Late in the 2011 holiday planning season, GSD&M came up with a "Share a Carol" promotion. The agency would record carols using four actors, then let Marshalls' customers online put them in front of a Google Maps Street View image of a friend's house--or most anywhere--and send a link.

Marshalls' marketing department liked the idea, so GSD&M scrambled to find developers to produce the Web app. But Marshalls' marketing department didn't have the computing capacity on which to run the app; provisioning servers in the company's data center would take time. So GSD&M turned to the Rackspace Cloud, which provided the servers to quickly launch the program and could also scale up if traffic spiked beyond projections.

As those projections rose 50% just before the project was launched post-Thanksgiving, GSD&M told Rackspace that it needed to double the server memory and storage. "In the cloud, we were able to change those resources on demand, as the concept changed," says Jerry Rios, GSD&M's CTO and senior VP of information. Getting that kind of variable capacity from Marshalls' IT organization would've run into "complications," he says.

Rios won't say what he paid for the Rackspace servers, but he says Marshalls' marketing could pay for it out of its own budget. GSD&M went from a small staging server during development to doubling the memory and storage of a production server when estimates rose, and then also extended the campaign six weeks because of its popularity. Without that ability to ramp up the IT infrastructure quickly, the promotion wouldn't have come off, Rios says.Price isn't always the top criteria when you need to move fast.

Another cloud infrastructure user, Broken Bulb Game Studios, is doing a different calculation--of dedicated cloud-based servers versus multitenant ones. The online game builder hosts 371,000 daily players of games such as Braaains and Miscrits of Volcano Island on 20 dedicated servers and 10 multitenant cloud servers, both managed by service provider SoftLayer. Broken Bulb is now moving all of its games to multitenant servers because it finds they provide the same reliability and manageability as dedicated servers at a lower cost.

"We are not venture-capital-backed. We can't tack on an extra $10,000 server whenever we want one," says CEO Robert Nelson. From its startup, Broken Bulb avoided building its own data center to concentrate on producing game code. It's moving 60 TB of data from dedicated servers to multitenant servers.

Broken Bulb uses RightScale as the front-end manager of those new cloud instances. RightScale has monitoring and analytics, so it predicts when a virtual server is running out of capacity and prepares another. RightScale services typically add 3 cents an hour to a service provider's regular charges.

One reason Broken Bulb is saving money is because it cut in half the RAM and processing power of its multitenant cloud servers compared with its dedicated servers, while still getting all the performance it needed. Nelson isn't sure whether SoftLayer manages its multitenant servers more efficiently than it could its dedicated servers, or if Broken Bulb had simply over-provisioned itself.

Coupa Software is typical of how cloud infrastructure has changed the way startups launch. The maker of procurement software got off the ground in 2006 focused on the system it wished to build rather than building out its own data center, using software-as-a-service and public cloud infrastructure services.

But it has also become a more savvy user of cloud services, cutting its cloud computing expenses almost in half over the past couple of years, says Sanket Naik, Coupa's senior director of cloud operations. To get those savings, it adopted Amazon's reserved instances--a commitment to a year of use plus an up-front payment in exchange for a lower hourly rate.

Naik wants Coupa to invest in technical people to build its core product, not to uncrate servers to be racked and stacked. And he thinks the price of computing in the cloud is going down, citing a March 6 price reduction from Amazon.

Each of these companies has a different yardstick for measuring the value of cloud computing infrastructure, one that doesn't hinge entirely on comparing the cost of public cloud services with the cost of on-premises computing. What they have in common is that each company would resist a you-can-buy-it-and-run-it-for-less argument. Cloud brings them an efficiency they don't think they could replicate in-house, and it lets their tech pros focus on new business projects over IT operations.

Can Cloud Go Big?

Yet the examples here also are fairly small-scale operations. It's when companies get larger that they start thinking their own dedicated data centers can replicate the efficiency and economies of scale of cloud providers for ongoing operations, so they can then harvest the savings from Moore's Law-driven hardware improvements.

Zynga is one example of that shift. The online game-maker launched its business on Amazon Web Services, and until recently ran 80% of its games (FarmVille, Words With Friends, Mafia Wars) on AWS. Now that those games have reached huge scale and more predictable volumes, Zynga plans to run more like 80% of its games on dedicated servers, run out of third-party data centers. It'll keep using AWS, but only for the bursty and unpredictable capacity. Zynga's now treating AWS like a premium-priced service for a specialty product--on-demand capacity--not long-term capacity. Of course, Zynga's not a typical enterprise IT operation, since it essentially runs one Web app on massive scale, not the mix of software most businesses face.

Lynden Tennison, CIO of $19.6 billion railroad company Union Pacific, runs a more traditional business but sees cloud infrastructure much the same way. The railroad business has fairly predictable business volumes, so UP doesn't see a lot of spikes in computing demand. It benchmarks its costs against cloud service prices and has found in-house more affordable. "I've always thought the cloud made some sense for midtier companies to embrace," Tennison says.

But even for big-company CIOs who think that way today, there are at least two big factors for them to keep an eye on.

The biggest one is competition. Amazon figured out a sweet business model if it can get long-term customers: It buys hardware and gets companies to pay for it over and over. But competition, which looks to be growing, will drive prices down. For example, Hewlett-Packard could prove to be a major force now that it has entered the cloud infrastructure market.

The other factor to watch is capability. Will conventional data center operators continue to match the capabilities offered by cloud vendors, which spend most of their time obsessing about hyperefficient operations?

Consider the degree to which cloud vendors automate operations. The typical enterprise has used virtualization to reduce its administrator-to-server ratio to as low as 1-to-35 or even 1-to-50. Microsoft's Chicago-area cloud data center has achieved a ratio of 1-to-6,000.

Energy use will be another test. Data centers have power usage effectiveness, or PUE, ratings that tell how efficiently they use electricity. The average enterprise data center uses twice the amount of electricity that's actually needed to do the computing--a typical PUE rating of 1.92 to 2.0. That extra power is consumed by lighting, cooling, and other systems.

By using ambient air cooling techniques and running warmer than average, Google's newest data centers deliver a PUE rating of 1.16; Yahoo's new Lockport, N.Y., data center has a PUE of 1.08; and Facebook's Prineville, Ore., data center has a PUE of 1.07.

Cloud data centers also are big users of open source software--Linux server operating system, Apache Web server, KVM, and Xen virtualization software--giving them a less expensive software infrastructure than the typical enterprise data center. Cloud centers pack in servers optimized--sometimes custom-built--for virtualization, then divide them up for multitenant use, reducing costs further. Cloud vendors spend the time to develop expertise in areas such as lower-cost virtualization software and energy-sipping server hardware because those efforts can scale even small savings across a massive installed base.

If cloud vendors can keep wringing out these cost savings of scale and efficiency, enterprise IT may find it increasingly difficult to match that performance. And then it just becomes a question of whether increased competition forces those cloud vendors to pass along their cost savings to customers.

Exactly when that magic mix of competition and capability makes cloud infrastructure prices irresistible to enterprise IT organizations isn't clear. For now, convenience and speed are the big drivers, but the pull of cloud efficiencies and savings will gain power over the next decade.

Research: 2012 IT Spending Priorities Survey

Our full report on IT spending is available free with registration.

Our full report on IT spending is available free with registration.

This report has data on the spending plans and budget impacts that IT pros expect from 16 tech projects, including public cloud, mobile device management, analytics and more. Get This And All Our Reports

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like