Docker is doing what once seemed impossible: providing common ground for Linux and Microsoft developers, say startup leaders.

8 Germ Hotspots In The Office

8 Germ Hotspots In The Office (Click image for larger view and slideshow.)

Docker is about to accomplish something that Steve Ballmer and Linus Torvalds couldn't, say StackEngine CEO Bob Quillin and CTO Eric Anderson. Docker appears on the cusp of providing a common ground on which Windows developers and open source Linux developers can meet.

Not that Docker is about to make them see eye to eye. On the contrary, there remain fundamental technical and attitudinal differences. But Linux developers have already voted with their feet in favor of Docker's form of Linux containers. Now with Microsoft and Docker pairing up to put Windows hooks into the Docker system, many Windows developers are likely to start using Docker containers as well.

Somewhere between half to three-quarters of the typical enterprise data center consists of Windows servers. "One of the biggest inhibitors for enterprises in implementing Docker was a clear lack of Windows support," noted Quillin in an interview with InformationWeek on the heels of the Docker/Microsoft announcement Wednesday. StackEngine is a Docker management and automation startup based in Austin, Texas.

[Find out more about Microsoft's Docker alliance. See Microsoft Brings Containers To Windows, Azure.]

Linux containers started out as a cloud phenomenon, a way to run multiple applications in close proximity on a single host. Google spokesmen boasted at June's Google I/O conference that it launches two billion containers a week. It shared some of its expertise by making its container launch and scheduling system, Kubernetes, available as an open source project.

Microsoft is offering a technical preview of Windows containers and parterning with Docker to make those containers work with the Docker formatting system. And that represents a huge step in the direction of enterprise DevOps, or bringing Linux and Windows development teams into closer synchronization with data center operations.

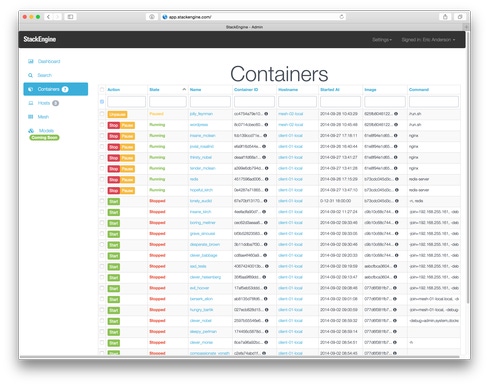

With Windows applications in the Docker picture, containers are likely to gain a role in the enterprise data center as well as in the cloud. StackEngine is bent on producing a container management system that does some of the same things for containers that VMware's vSphere and vCenter do for virtual machines. Right now, there's no comparison between the two in the degree of automation and management that's available. Virtual machines have a big edge.

For example, there is no live migration of containers, as there is with VMware's vMotion and migration processes of other virtualization vendors. Anderson said StackEngine understands how to do that, and he expects it to be a future part of its system.

The Kubernetes project, backed by IBM, Microsoft, Google, Red Hat, and others, will produce a container provisioning and scheduling system. But it still leaves a lot of management functions unaccounted for. After containers have been created and are running, there needs to be a tracking system that knows where each container is and what's in it. There needs to be a way to get containers to start, pause, or shut down.

To manage containers, an operations manager needs to know how much of a host's resources they're consuming: Is there capacity for more or should the existing load be spread out more? And what if IT needs to move some containers outside the data center into a public cloud service? These remain problems to be solved with containers, but to some extent platform-as-a-service systems, such as Red Hat's OpenShift, Pivotal's Cloud Foundry, and Active State's Stackato and Engine Yard, are starting to include containers in their configuration and deployment processes.

In many instances, however, Anderson said many of these functions still need to be performed by developers or managers skilled at writing their own code and using open source tools instead of through an automated system.

StackEngine started working on the problem nine months ago, and on Oct. 1, it announced the beta release of its StackEngine configuration, tracking, and change management system. "We'll integrate our system with Kubernetes and add scheduling features of our own," he said, while continuing to build out other management functions.

Scalable container management is going to be a big task, he continued. "Developers are putting multiple containers inside a virtual machine. But once you do, there's no single way to see or manage them," he said. Yet the modern style of development is to produce modules of code that represent specific services or parts of an application and run each as an independent container.

In the StackEngine system, it'll be possible to create software-defined networking links between the containers to combine them into a composite application, but Anderson said that work is still in progress. "It's an area of a lot of complexity. We can help there too," he said.

StackEngine consists of seven employees and is funded with $1 million in seed capital from Silverton Partners and LiveOak Venture Partners, two Austin early-stage venture-capital firms. Quillin said the firm will double its headcount over the coming year.

Docker and future container management systems "will help unify developers across platforms," since applications can be packaged and moved around with a single set of tools, Anderson noted. Developers like running containers because they multiply the power of servers. Where they might have run dozens of virtual machines on a single host, they can now run hundreds, in some cases thousands, of containers. Containers will also simplify some longstanding problems between developers and operations. Since a Linux application can run on a Windows Server (provided it's put in a Hyper-V virtual machine with a Linux operating system), operations may have more solutions to their old problem of getting greater utilization out of their hardware.

Operations managers will no longer need two different sets of tools to see and manage Linux and Windows workloads. And both Windows and Linux developers will be able to worry less about how their application will get deployed and more about the software they're trying to create.

The prospect of Windows containers "opens up Docker to the Windows segment within the VMware market -- a market larger than Linux -- as well as the entire Windows developer ecosystem. It's a win-win for the broader developer community," said Quillin.

InformationWeek's new Must Reads is a compendium of our best recent coverage of project management. Learn why etnerprises must adapt to the Agile approach, how to handle project members who aren't performing up to expectations, whether project management offices are worthwhile, and more. Get the new Project Management Must Reads issue today. (Free registration required.)

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like