Advances in phase-change memory could lead to a storage technology that

IBM Watson: Machine-Of-All-Trades

IBM Watson: Machine-Of-All-Trades (Click image for larger view and slideshow.)

On Tuesday, IBM said it had achieved a storage memory breakthrough that advances phase-change memory (PCM) in becoming a universal memory technology.

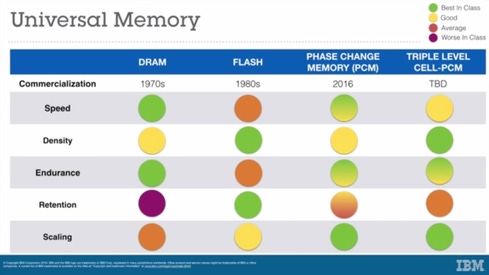

A universal memory technology should be suitable for most computing tasks and have few, if any, disadvantages. The fastest memory technology, DRAM, loses data when powered off. It's also expensive compared to alternatives. NAND flash memory retains data without power, but can't endure too many read/write cycles and costs more than disk storage. Magnetic disk storage is affordable and capacious, but also slow and ill-suited to computational demands.

IBM says it believes it can make PCM memory that approaches the speed of DRAM and can retain data like NAND flash over millions of read/write cycles. The company's researchers have managed to store 3 bits of data per cell in a 64k-cell array at elevated temperatures and after 1 million endurance cycles.

In an email, Haris Pozidis, manager of non-volatile memory systems at IBM Research in Zurich, said that in principle that translates to a potential tripling of PCM chip capacity, but mentioned that other factors come into play.

"Typically, the underlying circuitry (e.g. to program and read the cells) is more complicated with 3 vs. 1-bit/cell technology," said Pozidis. "As a result, more area of the chip may be occupied by the peripheral circuitry, which, for the same overall chip size, may shrink the area available for cell storage. Therefore, as fewer cells can be fabricated, typically the capacity may not be triple. However it ends up being pretty close to that ideal."

Pozidis sees PCM as a potential universal memory because it's fast, persistent, dense, and cost competitive. "Reaching 3 bits per cell is a significant milestone, because at this density the cost of PCM will be significantly less than DRAM and closer to flash," he said in a statement.

As examples of how the technology could be used, IBM suggests PCM technology could store a mobile phone's operating system, enabling it to launch in seconds, or it could keep entire databases in memory for time-critical financial applications.

Intel and Micron have a similar vision for their 3D XPoint technology, announced last year.

These two technologies are emerging amid industry concerns about the ability of storage technology to keep up the amount of digital content being stored. In a recent blog post, David S. H. Rosenthal, a Stanford researcher and veteran of Nvidia and Sun, predicted that storage will be much less free than it used to be.

If that's accurate, his forecast has major implications for many online activities that depend on abundant, affordable storage. It also suggests there may be a limit to the amount of digital history individuals and organizations can afford to maintain. If that's the case, what parts of history can we afford to forget?

To support his argument, Rosenthal points to industry trends and to the slowing of Kryder's Law, the storage industry's analog to Moore's Law. Moore's Law predicted the increase in transistor density in integrated circuits over time. Its basic accuracy up to this point has sustained the financial health of the semiconductor industry since 1965.

Kryder's Law isn't quite a formal prediction. Rather it's convenient shorthand for the view that we should expect similar gains for the areal density of magnetic disk drives -- a belief inspired by the period from 1990 to 2005, when hard disk capacities grew more than a thousandfold. Named after Mark Kryder, professor of electrical and computer engineering at Carnegie Mellon University, and former Seagate CTO, the so-called law came from the title of a 2005 Scientific American article.

It's a law that has already been violated by reality, which makes advances like those from IBM and Intel all the more important.

In a phone interview, Kryder said he didn't formulate the law bearing his name and he finds it somewhat embarrassing. Nonetheless, he's linked to it in part because, in 2009, Kryder co-authored a paper on the future of storage that supposed that "hard drives would continue to advance areal density at a pace of about 40% per year, which would result in a two-disk 2.5-inch disk drive that stores approximately 40 Terabytes and costs about $40."

That turned out to be an unrealistic expectation, given where the industry stands today. As Rosenthal explains in his blog post, storage density gains slowed noticeably by 2010 and haven't picked up. Kryder readily acknowledges being overoptimistic.

[Read IBM Watson to Fight Cybercrime.]

"We're at about 1.4 terabits per square inch in client space for PCs," said Kryder, adding that nearline storage is about 900 gigabits per square inch. "That's way off what would have been projected with the old 60% growth rate when I made those projections in that Scientific American article," he said.

But Kryder don't see this as a crisis for the storage industry. He points out that chip companies have been cheating to keep up with Moore's Law by increasing the physical size of chips when transistor density alone couldn't deliver desired performance increases. He also said that hard disk companies are doing the same thing by putting more disks or more disk heads in drive enclosures to compensate for lower areal density gains. The cost may increase as a result, but at least the capacity rises too.

"The demand for storage is enormous, and there are enough technologies, that I don't think we're going to be lacking for ways to continue to drive the cost down," said Kryder. "It may not be coming down as fast as it did historically, but you don't want it to go down any faster than you can process it. ... I think big data and the cloud will become a larger thing and that will drive more demand."

(Cover image: DKart/iStockphoto)

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like