Reassessing technology demands that emerged two decades ago and their influence on the current state of affairs for enterprises.

The immediate aftermath of Sept. 11, 2001 saw a rush to put technology to work on restoring some sense of normalcy and security amid tragedy. As the twentieth anniversary of the attack nears, questions arise about how technology evolved over the years. Current demands for digital security, detection, and disaster recovery differ substantially from the resources sought during America’s initial response to the attacks.

As InformationWeek covered 20 years ago, the days following the attack saw many businesses Assessing The Impact, combining personal concerns with corporate obligations to conduct operations as best as possible. At the time, a survey of 2,000 business-tech professionals indicated that 71% of respondents were willing to sacrifice privacy for increased protection from terrorist threats. Businesses also reassessed their contingency plans to see if they were Ready For Anything. Once the US military began retaliatory campaigns in response to the attacks, concerns emerged that put IT On High Alert of further aggression from terrorists who might target IT systems. Eventually, business and tech managers in the New York financial district in particular began to look at how they could Bounce Back, sorting out a recovery process under extreme circumstances.

In many ways, the current business-tech landscape is a wholly changed with security focusing intensely on hackers, possibly backed by other countries, who infiltrate infrastructure, commerce, and industry. The reveal in December of the cyberattack on SolarWinds put many organizations on notice for the potential for persistent digital aggressors.

Security concerns after the terror attacks of Sept. 11, however, brought calls to increase the use of biometrics such as facial recognition and retinal scanners to verify identities and potentially spot physical threats. There was significant interest in installing such resources at sensitive locations such as airports to screen passengers. The biometrics sector saw significant churn and consolidation of its players over the years as demand for the technology escalated. For example, fingerprint technology company Identix acquired facial recognition company Visionics but in turn was acquired and eventually became part of what is now Idemia.

Some organizations weighed installing biometric security and other measures to control access to large office buildings, power plants, and other locations believed to be at risk. The intent may have been to protect employees and resources not only from terrorists but any aggressor who might seek unauthorized access to their workplaces.

Sensor technology also garnered attention, with the intent of detecting hazardous materials or suspicious activity that might be warning signs of attack. It is not uncommon now to find sensors and software used to create “digital twins” to monitor infrastructure and equipment for general maintenance and upkeep.

Backup data centers also found their way into the spotlight after Sept. 11, especially as companies located in or around the World Trade Center in New York City’s financial district sought to maintain business continuity while coping with devastating loss of life. Jersey City, across the Hudson River, became an initial fallback position for numerous companies that lost colleagues as well as compute resources in the attack.

A variety of technologies that seemed novel 20 years ago have become more mainstream. Nowadays it is common to see smartphones use facial recognition, for example, to be unlocked by their owners. The spread of such technology has also led to questions about privacy, biases, and potential abuses of such data. This may include government entities, in the United States and abroad, seeking to use facial recognition to track down political dissidents and protesters.

Several years ago, the Knight Foundation introduced a competition to promote the development of technology resources that put data to work for the betterment of the populace -- without compromising human rights and privacy.

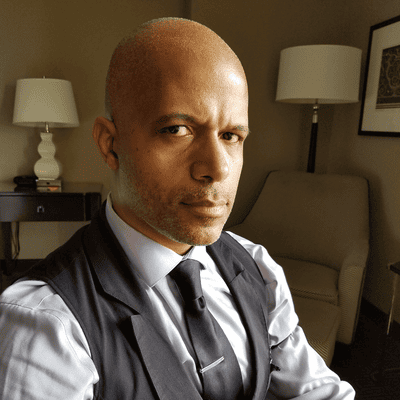

Though he was in high school 2001, Jonathan Lehr has seen a fair amount of the evolution of the enterprise tech scene in New York. He is co-founder and general partner of Work-Bench, an enterprise tech venture capital firm based in New York City. “[The market] moved from the on-prem model, which was prevalent at that time and about increasing your data center footprint,” Lehr says. “A decade after 9/11, that was when the banks of the world started saying, ‘Hey, we really got to rethink this.’”

The advent of the cloud led to exploring how to reduce data center reliance, he says, with banks leading the way at times, followed by large pharma and media. The emergence and rise of AWS, Google Cloud Platform, and Microsoft Azure set the stage for a cloud-first world, Lehr says. Disaster recovery has evolved via the cloud with the capacity for failover capabilities in multiple datacenters in different geographies, he says. “Now there’s disaster recovery plans and software in the cloud.”

Individual behavior over the decades also became increasingly connected to personal devices and mobile access. “The dynamics changed,” Lehr says. “When you had a data center, you had people on call 24-7 to go fix that specific server, to go put hands on keyboards at a machine. In a world of cloud-first, you don’t have that and you cannot do that.”

In a future where even more connected devices are expected to exist, he says maintaining continuity of services will be increasingly crucial. “We’re going to need to be able to handle downtimes better,” Lehr.

Innovators in enterprise technology now aim to solve pain points that extend far beyond Sept. 11 and even the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. “A big area that we’ve seen is around third-party risk,” Lehr says. “Two decades ago, there were just a handful of vendors that would deal with as a large company. In the world of SaaS-first companies, you have more point solutions that ever.” Managing the risk of onboarding such companies has led to the emergence of startups such as Viso Trust, he says, which automates parts of that third-party cyber risk. Work-Bench is an investor in Viso Trust.

The desire for safety and security naturally has not vanished over the past two decades, but the focus of enterprise technology has clearly shifted to more routine concerns. Model monitoring in machine learning has emerged as a top-of-mind issue, Lehr says. “If you think about AppDynamics, Datadog, and traditional application and infrastructure monitoring, now with machine learning more prevalent than ever, how do you monitor your models for drift?” This can have business impacts, he says, for example as organizations aim to eliminate biases in their automated models -- such as a husband getting approved for a credit card while a wife in the same household is not solely because of gender.

Related Content:

SolarWinds CEO Talks Securing IT in the Wake of Sunburst

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like