Verizon Wireless is in hot water with security and privacy advocates regarding unique identifier headers that function as what one EFF expert calls "perma-cookies."

Verizon Wireless is tracking more than just your bandwidth usage these days -- it's also spent the last two years collecting data on your mobile web searches, the apps you use, and the websites you visit, according to security researchers.

Many websites monitor users' web activity: Facebook recently announced plans to track users' actions between devices and share with advertisers when an ad or promotion leads to a purchase. Google uses cookies similarly to track users across the web, too.

But Verizon Wireless's method, which it calls a Unique Identifier Header (UIDH), can't be deleted, unlike a cookie, and travels across the web with users, even if customers opt out. Security and privacy experts say this new form of tracking has potentially dire consequences for users' online privacy.

"Customers are used to the idea of cookies on the web and understand the various protections you can apply like clearing cookies, private browsing, and Do Not Track," said Jacob Hofmann-Andrews, staff technologist at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, who noticed the UIDH last week. "But this new identifier doesn't work like any of that -- this allows advertisers to create a persistent profile tied to your real-world identity that is impossible to get rid of."

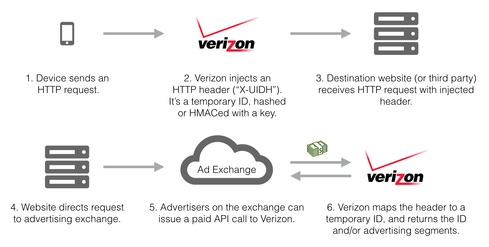

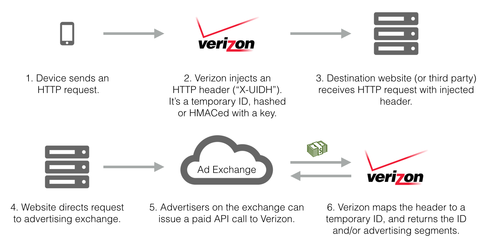

Understanding the UIDH

The UIDH is a string of characters that the company inserts into data that flows between customers and the websites they visit, Hofmann-Andrews said. He likened the UIDH to a "perma-cookie," which any web server you visit can read and use to build a profile of your activity -- without your consent.

Figure 1:  (Image: Jonathan Mayer, Webpolicy.org)

(Image: Jonathan Mayer, Webpolicy.org)

Verizon Wireless's UIDH reportedly has tracked users since 2012, but was discovered only recently because it's so hard to observe, Hofmann-Andrews said in an interview.

"Because the header is injected in the network layer after the request leaves the device, there's no way with the device itself to tell what's going on," he said. "In order to notice this, you have to operate the device and the server you're talking to, and in addition to that, the server has to be configured to log all headers, which is a rare configuration."

All Verizon Wireless customers were automatically opted into sending the header based on the company's terms of use policy, Hofmann-Andrews said.

[Popular social apps may track your every move. Read Location Tracking: 6 Social App Settings To Check.]

The UIDH is part of Verizon's Relevant Mobile Advertising program, which shows customers ads on websites and apps based on information such as your address, demographic information, and interest categories. They pair this data with the UIDH, which the company says "may allow an advertiser to use information they have about your visits to online websites to deliver messages to mobile devices on our network."

In a statement to InformationWeek, Verizon Wireless said that it changes the UIDH on a regular basis to prevent third parties from building profiles against it, though it did not disclose the timeframe. Details in its Relevant Mobile Advertising FAQ imply that users are given one ID, at signup: "In addition, we will use an anonymous, unique identifier we create when you register on our websites," it says.

Security researcher Kenneth White set up a website that checks whether Verizon -- or other wireless carriers -- have attached a UIDH to your

web browsing. He found instances in which AT&T customers had a similar tracker attached to their web history, and, inexplicably, that not all Verizon Wireless customers were affected by a UIDH.

In tests, White found that despite his location -- including 500 miles from home for a business trip -- and despite different IP addresses and carrier networks, his ID has remained the same. His website has logged more than 350,000 visits, he said.

"These things seem to survive IP address changes, carrier changes, and geography changes," White told InformationWeek in an interview.

And it's not just affecting consumer accounts, but enterprise Verizon Wireless accounts, too.

"If you surveyed a sample of CIOs whose organizations use Verizon and asked if they were aware that their wireless provider is injecting persistent world-readable cookies into users' web traffic, there would be a great deal of concern," he said. "Organizations are not paying for their employees to be captive eyes for enhanced 'cross-device brand experiences.' "

Your opt-out options

Verizon says that it does not use the UIDH to track where customers go on the web -- a moot point, the EFF's Hofmann-Andrews said, because third parties can still track these IDs.

"There's a key distinction here: There's what Verizon does under that program, and what the program allows others to do," he said. "Verizon has some controls, which dictate whether an advertiser can ask Verizon for more information based on the header. If you opt out, third-party ad networks with no relation to Verizon can still use this as a perma-cookie to create a long-term browsing history."

Opting out of Verizon's Relevant Mobile Advertising Program means the company won't share personally identifiable information with its partners, but that doesn't prevent the headers from being transmitted. This means that both partner and external ad networks can still follow your ID across the web and build a profile about you based on this information.

You can opt out by logging into your Verizon account and adjusting your privacy settings. Opting out also means you won't receive targeted advertising from Verizon.

Verizon said in a statement that it will still transmit the UIDH even if you opt out because it's "also used to recognize and authenticate subscribers on behalf of Verizon's own or others' applications and services. ... In essence, the UIDH provides a passive validation confirming that the customer is who s/he says."

Web tracking: a dangerous road

Your online activity can reveal a lot about you, said Andrew Sudbury, CTO and cofounder of privacy software company Abine, including where you live, where you work, where you shop, whether you have children, and whether you may have a medical condition.

"This kind of information has lots of uses for insurance, marketing, credit scoring, and political leanings," he said in an email. "And we've already decided as a society that some of this information should be protected. Look at the controls around credit reporting and health information (HIPPA). This is very private information that, if monitored, can have a chilling effect on free speech, political activity, and even innovation."

Pam Dixon, executive director at the World Privacy Forum, said that while some people may not care that their searches for a restaurant or a new car are tracked, they should understand the implications of

tracking more sensitive search topics.

"This information on you could be held long-term, depending on Verizon's partners and whether it's sharing web browsing information with data brokers and data resellers," she said in an interview. "And when it comes to sensitive searches, people should be able to search for this stuff without fearing for reprisals based on what they're looking for. This may crimp people's style and their willingness to search for things on the Verizon network."

Verizon did not answer InformationWeek's request for the names of its data broker and data reseller partners.

What you can do

Verizon Wireless's UIDH renders traditional privacy mechanisms -- such as clearing cookies, browsing incognito, and private browsing -- useless, the EFF's Hofmann-Andrews said. And while the header will follow you to most websites, it will not track you on websites that use https, he said.

There are two ways to circumvent Verizon's use of the UIDHs, though neither is especially practical, Hofmann-Andrews said. The first is to always browse the web on your device while connected to WiFi instead of relying on cellular data, since WiFi enables you to bypass Verizon servers. The second is to use a VPN on your device, which insulates the user from the carriers and Internet providers -- but is a solution that he says should be unnecessary.

"Users shouldn't have to install a VPN to protect themselves. When you use a VPN, you're trusting that VPN not to modify your traffic," he said. "You're buying privacy as an add-on, but it should be built into your service."

The preferred solution, privacy experts said, is for Verizon to cease -- or at least modify -- its use of the UIDHs.

"We think Verizon needs to stop modifying users' Internet connections and reengineer this header immediately so it only gets sent when a user explicitly opts in," Hofmann-Andrews said.

"The thing that really strikes me is even the smartest and most conscientious consumer would have had trouble detecting this," said the World Privacy Forum's Dixon. "It's very discouraging for people who are trying hard to stay safe online."

Considering how prevalent third-party attacks are, we need to ask hard questions about how partners and suppliers are safeguarding systems and data. In the Partners' Role In Perimeter Security report, we'll discuss concrete strategies such as setting standards that third-party providers must meet to keep your business, conducting in-depth risk assessments -- and ensuring that your network has controls in place to protect data in case these defenses fail. (Free registration required.)

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like