The Truth About Why Stores Track You

Apple's iBeacon and other "contextual awareness" technologies might soon pop up on your smartphone as shopping advice. That's not as frightening as it sounds.

When I talk to people about indoor-tracking tools like iBeacon, which Apple launched at its US stores last Friday, they're both fascinated and frightened. They quickly appreciate how helpful a connected world can be when it knows where you are and what you're doing. But the steady of stream of news about privacy intrusions -- mostly by the NSA -- makes them wonder if the cost of allowing access to more personal data is really worth it.

Apple introduced the iBeacon feature as part of the iOS 7 launch in September. It makes use of the iPhone's Bluetooth radio to communicate with other iOS 7 devices as well as compatible sensors placed at strategic spots around Apple stores. Among other things, the close-range nature of Bluetooth can be used to pinpoint a shopper's whereabouts to deliver location-specific messages. For example, someone with an older iPhone might get a trade-in offer while checking out the newer models.

Location is the cornerstone for contextual awareness, a collection of efforts aimed at giving our smartphones the tools they need to begin making timely, relevant suggestions and even take action on our behalf. Understanding that we're standing in front of the smartphones rather than the tablets is an important piece of the puzzle.

[Read how one clothes chain keeps inventory moving: How Gap Connects Store And Online Channels. ]

Apple isn't the first to implement a Bluetooth indoor-tracking system. For example, the Miami Dolphins' Fin Club app uses Gimbal -- a set of location-aware developer tools from Qualcomm -- to send in-stadium discounts to fans. In fact, Apple isn't even the first to outfit stores with its own iBeacon platform. Shopkick is motivating shoppers inside several Macy's stores with reward points and special offers based on where they are.

Contextual awareness isn't just about commerce, though it would be a benefit if all it did was offer up ads that we care about. (A philosophical question: if we receive pushed ads that actually interest us, are they spam?) There are efforts under way by transportation authorities to deliver updated train schedules when you're standing near the track and by museums to push information about the artist when you're admiring a painting.

Understanding where we are at the moment is a big step on the way to empowering our smartphones to understand us, but it's just the first step. There's a lot of innovative work underway that promises a suite of novel benefits -- but require access to even more of your personal information. Instead of showing you an ad for the cordless drill you're admiring, for example, the app on your phone might instead point you to a scarf in another corner of the store because it knows your spouse has a birthday coming up. And it knows you haven't bought her anything yet.

The demand for insight into ever-more pots of your personal information is increasing just as the backlash from ongoing NSA revelations is making consumers more aware of the digital fingerprints they're leaving behind, and increasingly wary of those with access. Privacy has become such a front-and-center issue that a group of companies with access to mounds of personal information -- and who stand to lose a lot if the public's posture on privacy continues to stiffen -- this week lobbied the federal government to reign in espionage. You don't see Apple, Google, Microsoft, and Facebook coming together on much of anything these days, so it's clear they all understand what's at stake for them.

I like to say that we won't need to worry about our digital privacy precisely because we're all worried about our digital privacy. If the NSA leaks have taught us anything, it's that there's a right way and a wrong way to collect personal data. Tell us what you want to collect, ask our permission to collect it, and give us something in return that we find of value and most of us will be on board. Skip any of those steps and we're not.

It's why customer backlash forced Nordstrom to pull its in-store customer research, which surreptitiously tapped the WiFi signal from customers' phones to track them around the store. And at the other end of the spectrum, it's why Shopkick has been able to attract more than 6 million downloads of its tracking app by offering discounts and reward points.

I'm producing a conference next spring that's bringing together industry leaders in this fast-developing field to hash out these and other contextual-awareness issues. The conference, called MarketsofOne TechSummit, will be held April 10, 2014, at the Four Seasons in Palo Alto, Calif.

In the meantime, there's no need to worry about all these new requests for our personal information. Provided we're all worried about it, that is.

Apply now for the InformationWeek Elite 100, which recognizes the most innovative users of technology to advance a company's business goals. Winners will be recognized at the InformationWeek Conference, March 31 and April 1 in Las Vegas.

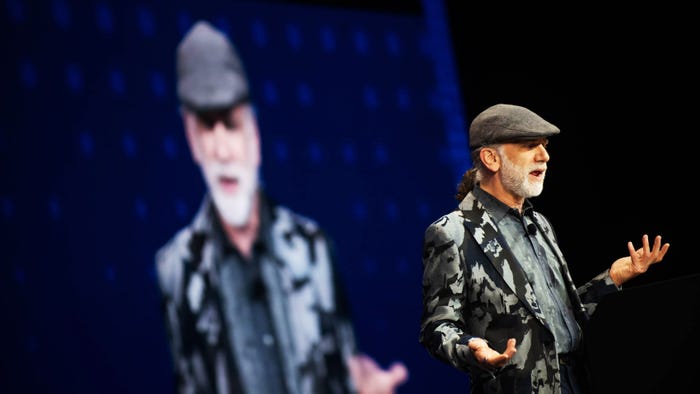

Mike Feibus is principal analyst at TechKnowledge Strategies, a Scottsdale, Ariz., market research firm focusing on mobile client technologies. You can reach him at [email protected].

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

How to Amplify DevOps with DevSecOps

May 22, 2024Generative AI: Use Cases and Risks in 2024

May 29, 2024Smart Service Management

June 4, 2024