Employee Surveillance: Business Efficiency Vs. Worker PrivacyEmployee Surveillance: Business Efficiency Vs. Worker Privacy

Legal scholars argue that new laws are needed to define the parameters of acceptable workplace monitoring and to ensure respect for personal privacy.

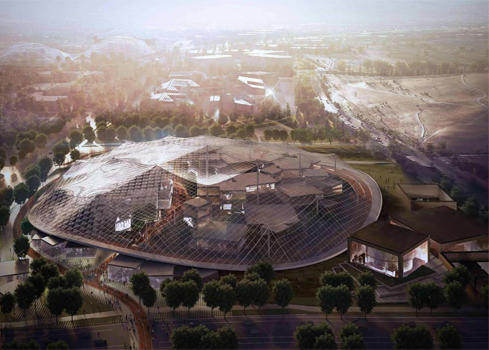

Google's Next HQ: Modern, With Retro Flairs

Google's Next HQ: Modern, With Retro Flairs (Click image for larger view and slideshow.)

Supervision of employees used to have limits. Managers simply couldn't watch every employee all the time.

That's no longer true today. As discussed in a draft of a forthcoming California Law Review paper, technology enables pervasive and invasive monitoring. And as dispersed workforces become more common, there's more incentive to rely on technology as an alternative to face-to-face interaction with managers.

"Now, with the advent of almost ubiquitous network records, browser history retention, phone apps, electronic sensors, wearable fitness trackers, thermal sensors, and facial recognition systems, there truly could be limitless worker surveillance," the paper says.

Companies have a right and an obligation to operate efficiently. Some oversight of employees is undoubtedly necessary. But as legal scholars Ifeoma Ajunwa, Kate Crawford, and Jason Schultz argue in "Limitless Worker Surveillance," unrestrained surveillance raises privacy and discrimination concerns.

Sometimes it's easy to see when workplace surveillance goes too far. The paper cites the outrage that followed at The Daily Telegraph in the UK when workers discovered "OccupEye" sensors that had been placed under desks to track worker attendance under the pretense of gathering energy efficiency data. The outcry ultimately ended the project.

But the issue can be more nuanced. The paper refers to a May 2015 Ars Technica report about a woman who was fired after she deleted the Xora employee tracking app from her phone. Her legal complaint asserts that managers monitored her movements even when not at work.

The defendant in the case, Intermex, responded to the woman's allegations in July last year, arguing that the plaintiff had consented to the use of the Xora tracking application on her company-provided phone and that she had violated company policy by failing to turn off the Xora app (now called StreetSmart by ClickSoftware) during non-working hours despite being trained to do so.

What's more, Intermex claims she worked for another company while working at Intermex, holding two full-time positions in violation of Intermex's conflict of interest policy. The plaintiff's complaint claims that the woman's supervisor had accepted this arrangement so that her medical benefits from her prior employment would remain in effect until coverage from Intermex took effect.

The two paries settled on Oct. 30, 2015, and the case was dismissed thereafter.

While the line between appropriate and intrusive workplace surveillance may not always be obvious, the paper points out that surveillance for the sake of business efficiency can have the opposite effect. "Too much monitoring creates stress, fear, and incentives to 'beat the system,'" the paper says.

The authors argue that workplace surveillance has moved beyond a legitimate interest in productivity to shaping individual behavior. As examples of this trend, they cite productivity apps and corporate wellness programs.

Apps like Xora, for tracking employees, and BetterWorks, which encourages productivity through the gamification of project goals, normalize and incentive surveillance, the paper contends. They make monitoring seem progressive by advancing the conceit that surveillance leads to innovation and growth, while ignoring the cost to individual rights.

Are you prepared for a new world of enterprise mobility? Attend the Wireless & Mobility Track at Interop Las Vegas, May 2-6. Register now!

Wellness programs raise related concerns about workplace discrimination and data privacy, particularly since some companies now make them mandatory. Companies that collect health data from wearables can do so without oversight, the paper notes, and that data, when it flows through a corporate-owned device, belongs to the employer rather than the employee.

This all may sound abstract, but behavioral data can have specific employment consequences. For example, in nine states employers can fire workers for smoking outside the workplace.

The authors state that worker surveillance is limitless because no federal laws directly address the issue. Thus they propose new legislation, an Employee Privacy Protection Act, that would limit workplace surveillance to actual workplaces and would prohibit agreements that waived such privacy rights. They also suggest a similar law is needed for worker health data.

"While employers have a reasonable interest in ensuring the productivity of their workers and in dissuading misconduct in the workplace, that interest does not outweigh the human right to privacy and personal liberty in domains that have been traditionally considered as separate from work and the workplace," the authors conclude.

About the Author

You May Also Like